*Song Keepers,* Page One

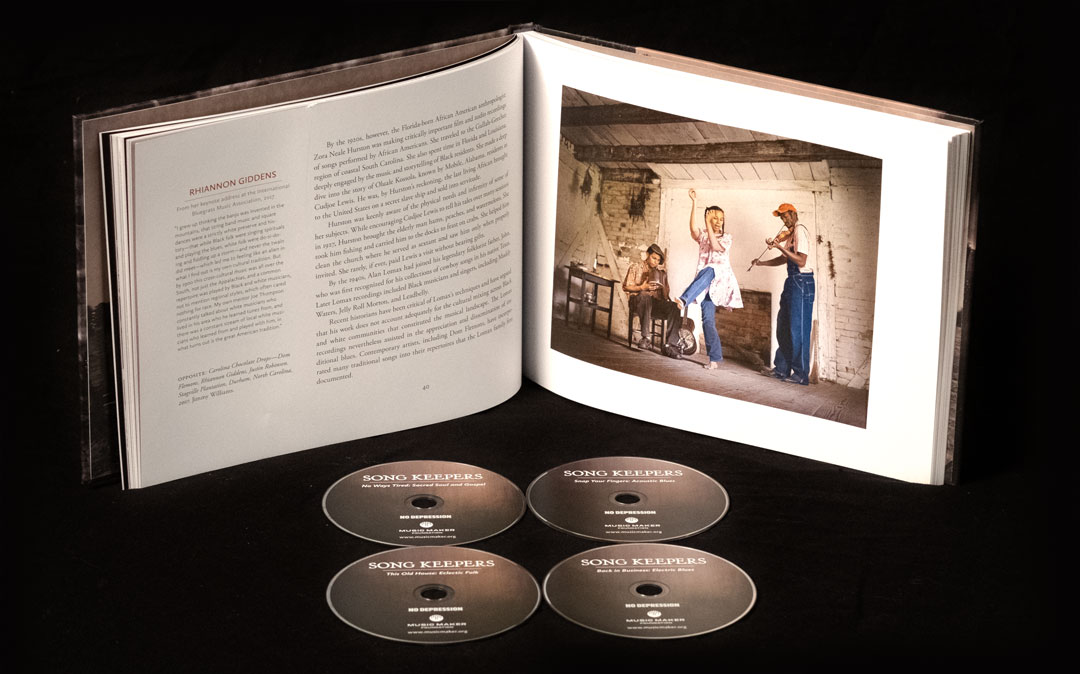

The first page of a book, if it’s good, sets the table for what follows. At the risk of sounding immodest, we think our forthcoming book Song Keepers has a lot to offer readers and listeners, and that on its first page you can already tell. So let’s analyze the photo and the text of Song Keepers‘s first page . We do this as a slight tease, in the humble wish that once you start unpacking the delights and insights of the first page, you’ll want to read and listen (there are four beautiful CDs in every set) to the whole thing!

Let’s start with the photograph. There’s Freeman Vines, mystical luthier on the left. He’s in dark shades, but you can tell he’s returning the glance of the camera (wielded expertly by Tim Duffy), staring it down at least as much as it does him. He’s holding a cigarette in his left hand, with an insouciance that belies a whole lifetime raised in tobacco country out in Eastern Carolina. He’s dressed casually but with great style, his shirt perhaps a nod to the colorful Aloha shirts worn by characters from the TV in his artist’s studio. Hints of his work are strewn around him — books, guitar bodies in various states of decomposition, an amp just out of frame. This amp is connected to an electric guitar on the lap of Altrice Speight’s son, himself on his mother’s lap. Notice he’s in a Superman shirt; notice her smile as she looks over her son’s shoulder. He’s wearing clean Vans, his heels arched in concentration. His Mom’s feet are in the same position, forming a symbolic familial symmetry. Notice the boy strums the guitar while his mother frets the neck for him. This picture stands for Song Keepers: these are the people we want to support and with whom we try to partner.

This brings us to the first page of text, written by Georgann Eubanks. Now the book features interviews with Grammy winners Taj Mahal, Dom Flemons, and Rhiannon Giddens, and former director of the National Endowment for the Humanities, William Ferris. It features chapters on the genesis, mission, music, and artists of Music Maker Foundation’s past thirty years. But on this first page, there are already premonitions of all this and more. Let’s gloss some of the key moments and see:

American roots music still flows through communities large and small in the South

Blues, gospel, folk, and indigenous music is not a thing of the past, killed by postmodern technology, but a living thing like a river.

Roots music has been carried forward by legions of self-taught players, church-raised performers, family bands, side men, backup women, and solo artists who simply can’t help from singing.

The musicians Music Maker provides assistance to are not well-known or rich. Their music comes out of the institutional forms their daily lives are embedded within: they are vernacular performs, and make music of their own devising in worship, with their parents, and/or brothers and sisters. And they sing not only for acclaim or money, but also because music is a part of any life worth living. As Georgeann goes on to say, the music “comes from the everyday experiences of every day people.”

They shine a light on who we are as Americans and what we have come from– Black, white, Indigenous, and immigrant.

Against xenophobic, supremacist notions of what makes an American, the artists of Music Maker stand for a more diverse, truthful figure for what America was and is. They represent the sometimes unacknowledged sources of American prosperity, and their music represents American ideals in all their complexity in a way that has sometimes been elusive in historical practice.

So on this first page, it’s hopefully clear why we called this book and box-set Song Keepers: in our supporting role, we help keep these songs and performers going, which they keep going in the first place, crafting and playing them. We’d be honored if you checked out Song Keepers and become (or continue to be) a song keeper yourself.

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.