My Blues Honeymoon With Music Maker’s “Raiders of The Lost Spark”

By Cree McCree.

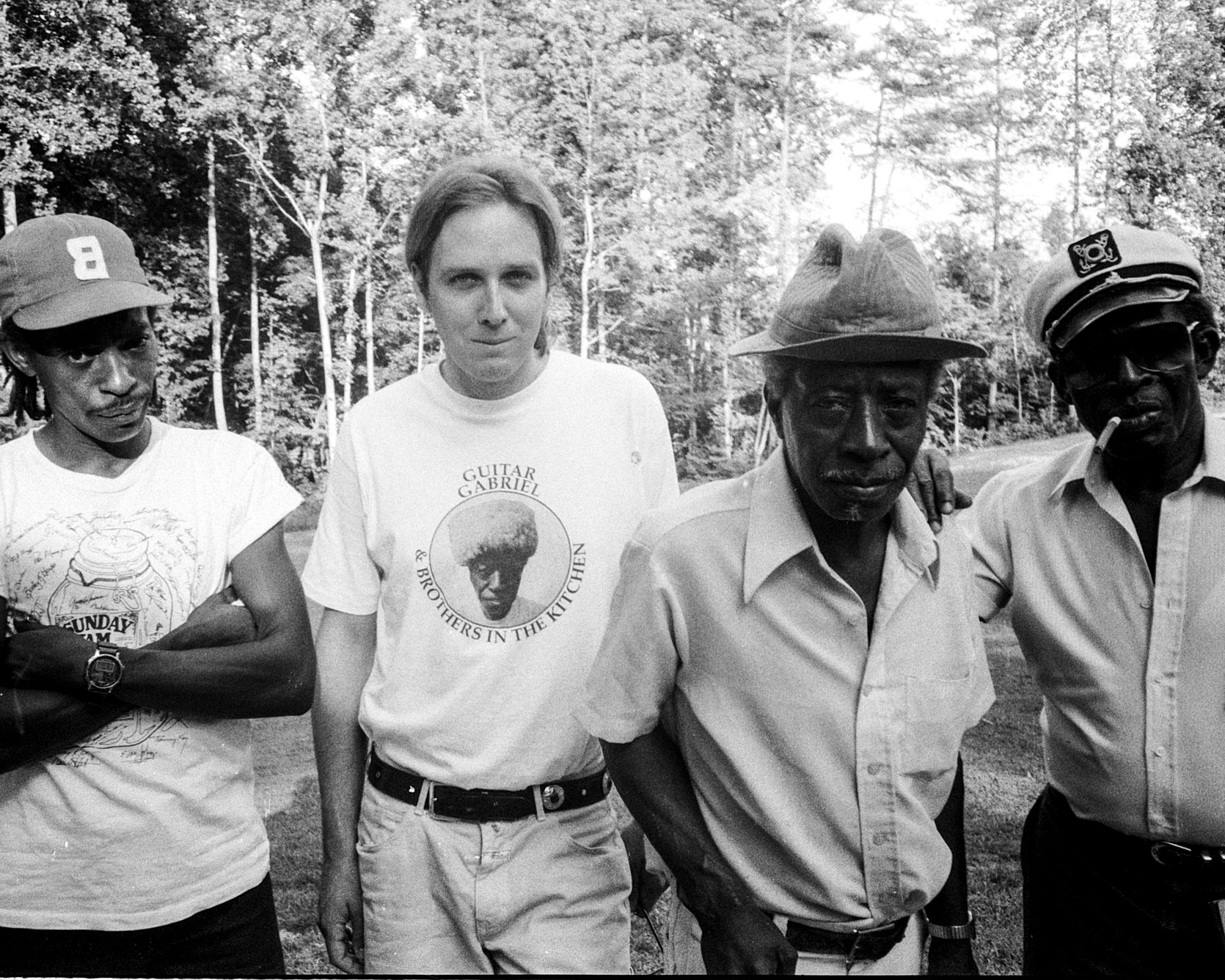

In 1995, I celebrated getting hitched to guitarist Donald Miller with an all-star lineup of founding Music Maker artists — Guitar Gabriel, Willa Mae Buckner, Macavine Hayes and Captain Luke — as the guests of Music Maker founders Tim and Denise Duffy, who gifted us with a long, memorable weekend filled with music, moonshine and laughter.

It was pure serendipity that our September courthouse wedding in Edenton, North Carolina, happened to coincide with that year’s Bull Durham Blues Festival, where several Music Maker artists were scheduled to appear. But it dovetailed perfectly with my own journalistic mission to document foundational blues artists, and Music Maker, then just a year old, was already on my radar. While we were making our wedding trip plans, I was in the process of completing “Raiders of the Lost Spark,” the article that follows, which ran in the October issue of the national alt-music magazine huH. So when Tim and Denise offered us an all-access pass to the fertile crescent that gave birth to Music Maker, and the chance to meet the inspiring artists I’d only interviewed by phone, we quickly made it the centerpiece of our honeymoon.

It was raining at the festival grounds when Tim and Denise arrived with a van full of aging Music Maker artists, including a wheelchair-bound Guitar Gabriel. But though it continued to drizzle on and off, everyone’s spirits remained high while we feasted on fried catfish po-boys backstage and Willa Mae flirted outrageously with Donald, much to his delight. When it was showtime, the Duffy brothers gave Guitar Gabe a royal escort to the stage, where he opened a Music Maker set that quickly expanded into a full band, showcased several of Willa Mae’s hoochy koochy numbers and left the crowd hollering for more. And that was just the appetizer for the full honeymoon feast.

Saturday kicked off with a visit to Captain Luke, who regaled us with Kingfish stories and showed off his latest collection of hammered beercan folk art (I still prize the Old Milwaukee ashtray I bought that day). He also gave us some homemade peach wine, which sounded delightful but tasted like industrial strength vinegar. Not so top shelf apple moonshine Tim broke out ceremonially to toast our nuptials at the Duffys’ own house party. That ‘shine went down so smoothly that night remains a blur, though I do recall Donald breaking out his 12-string for an impromptu jam session with Tim and some of the other guests.

Come Sunday, we rallied to “go to church,” as Donald puts it, by visiting one of Tim’s favorite “drink houses” in Winston-Salem after picking up Guitar Gabriel at the local old folks home. Like the juke joints of the Mississippi Delta, these rowdy house parties are the heart of a marginal community whose soundtrack remains the blues. Unlike the Delta’s well-documented jukes, however, which have become a mecca for white blues buffs, the Carolina drink houses aren’t in any guide books. So it’s not surprising that the regulars were initially wary when we arrived.

“The entire drink house shut down when we first pulled up, because they saw a van full of white people,” recalls Donald. But as soon as Guitar Gabe got out in his wheelchair, they welcomed us.

Macavine Hayes, who we’d picked up en route, rolled Gabe out to a place of honor in the backyard, looking spiffy as ever in a white cap. To get the party started, Tim rigged up a couple of small amps and pulled out a vintage Telecaster, which, despite its pedigree, had “a very dull sound,” much to Donald’s disappointment (and Tim’s suspicions). “We had to work hard to make it work, but since it was all we had, everyone made it work.”

Gabe was first up at bat on the Tele and coaxed some sweet sounds out of it with his long, graceful fingers, backed by Macavine on his own guitar. Then Tim took a turn on the Tele with one of the drink house regulars blowing harp for a few tunes before handing it over to Donald. After trading some preliminary licks, Macavine and Donald rocked the backyard with a sing-along, dance-along “Knock On Wood.” That spirited community throwdown served as a finale to our ad hoc drink house revival meeting, a highlight of a Music Maker honeymoon that blessed our union with the blues.

Learn how Tim Duffy’s “Raiders of The Lost Spark” first ignited Music Maker’s mission in the article that follows:

Raiders of The Lost Spark [huH, October 1995]

A former bus-driving contortionist who sleeps with a 17-foot snake at seventy something? A resentful old hermit whose son wields a mean razor blade? North Carolina field recorder Tim Duffy has seen it all during his treasure-hunting quest to document an obscure, fleeting, and beautiful culture for his own Music Maker label. Cree McCree investigates the blues detective and the music he’s revived from the dead.

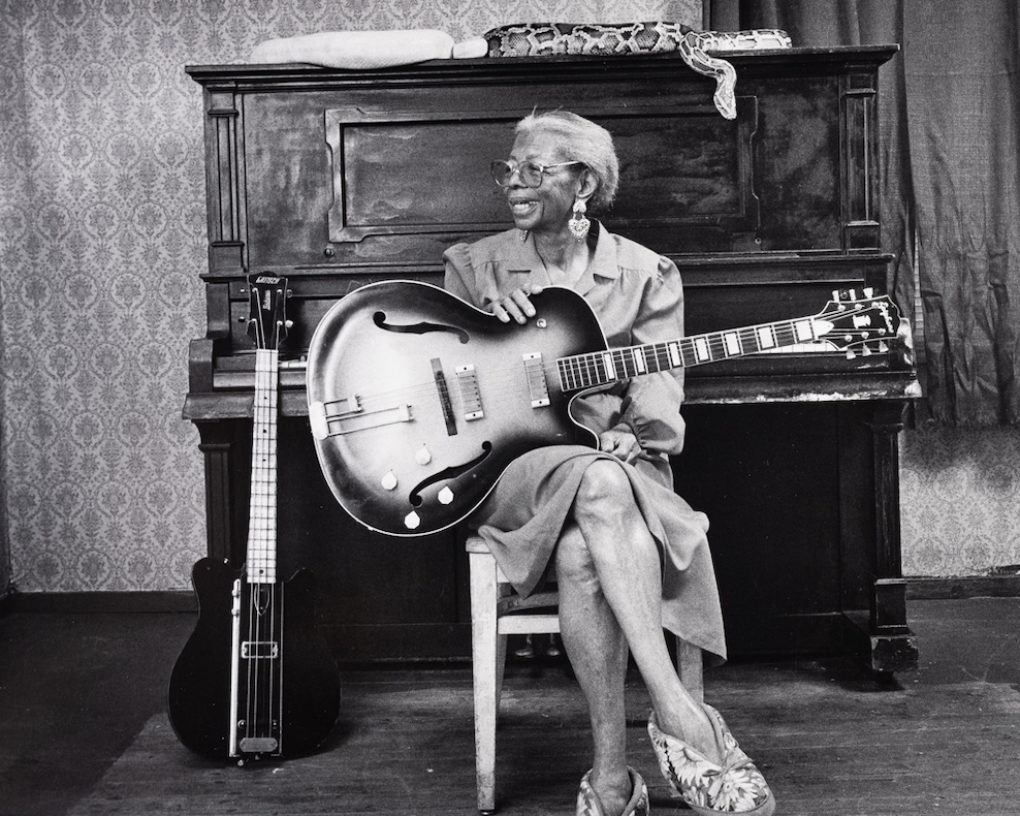

She’s raised eyebrows with sexy songs dripping with innuendo. She’s raised temperatures with erotic-fantasy dances. And what she does in her own bedroom is definitely kinky. Madonna Ciccione, meet your great-grandmother, Willa Mae Buckner: the “Wild Enchantress” of the all-Black tent show circuit of the ‘30s and ‘40s, where her boogie-woogie blues were scandalously “blue” and she wrapped her bronze-painted body with undulating pythons — including 17-foot Big Jim, who was still sharing her bed when Willa Mae turned 70.

“I’ve enjoyed Madonna’s efforts to get where she is today,” says the sassy septuagenarian, who sings some of her old “dirty songs” on a new CD that documents A Living Past: acoustic blues recorded in the living rooms, kitchens and nursing homes of all-but-forgotten artists. “Madonna’s story is different than mine,” adds Buckner, whose resume includes stints as a carnival contortionist, session bass player, city bus driver in Winston-Salem, NC — and, most recently, Music Maker recording artist. “But we both stuck with it, you know.”

So did Tim Duffy, a young white musician/folklorist turned amateur detective and field recorder. Now based in Winston-Salem, after stints in Africa and Appalachia, Duffy has spent the last few years in and around the Carolinas tracking down long-retired artists like Buckner and Captain Luke, whose repertoire ranges from Kingfish stories and an onomatopeic jaw harp to basso profundo vocals. Duffy uncovered one old-timer after another, each leading to the next in a chain reaction that eventually became the Music Maker Relief and Recording Foundation, which now funnels sales from CDs directly into the medical bills, roof repairs and living expenses of a dozen aging artists.

But it all began with Duffy’s dogged pursuit of Guitar Gabriel, a legendary bluesman supposedly killed in a house fire years ago.

Determined to honor the deathbed request of his mentor James “Guitar Slim” Stevens, who instructed the young archivist to “find Guitar Gabriel,” Duffy followed a convoluted trail to the rowdy “drink houses” concealed behind closed doors in the crack-infested projects of East Winston-Salem. Like the juke joints of the Mississippi Delta, where the liquor’s cheap, the tales are tall and your luck can change as fast as a chord change in a 12-bar, these nonstop house parties are the heart of a marginal community whose soundtrack remains the blues. Unlike the Delta’s well-documented jukes, however, which have lately become a mecca for white blues buffs, the Carolina drink houses aren’t in any guide books.

“I stumbled into this whole hidden culture,” recalls Duffy, who got shot at by wary locals and hassled by equally wary cops. And when he finally flushed out a very-much-alive Guitar Gabriel, “it was a war.” New recruit Captain Luke became Duffy’s bodyguard during an all-out battle with Guitar Gabriel’s family, who were dead set against any efforts to revitalize his career.

“No one in the projects wants to see anyone go up, because it breaks up the structure of the community,” Duffy explains. “His son tried to kill me with a razor blade.” Nor was he welcomed with open arms by Guitar Gabriel himself, who’d been holed up with his axe and a bottle since 1970, when his regional-hit single “Welfare Blues” netted him less than zero in a classic music-biz burn.

“Gabe was intentionally, and understandably, mistrustful of the whole world,” he says of their initial meeting in 1991. “He had the most terrible case of the blues I’ve ever seen.”

Guitar Gabriel spat it out in “Dr, Buzzard”: “Whoa, I feel like a broke down engine, I swear done lost its driving wheel.” But as Gabe later observed, “blues takes a lot of animosity out of your heart,” and the best cure for the blues was The Blues.

“Once we started playing together, we began building a relationship that evolved into a marriage of sorts,” relates Duffy, who’d bridged similar cultural gaps while making field recordings in Kenya. Thus the sheepskin hat bequeathed him by Kikiyu tribesmen ended up on the head of Guitar Gabriel, who wore it like a crown on the cover of his 1993 Duffy-produced CD, Deep in the South. And it never looked more regal than at Carnegie Hall, where he received a standing ovation after being named Living Blues Comeback Artist of 1994.

“Whenever you wear this hat, it gives you a feeling of what you are representing,” explains Gabe, great-grandson of a slave, grandson of a sharecropper, and son of an itinerant blues man and “sideshow geek” called Razorblade (whose razor blade and glass-eating act Perry Farrell would have booked in a hot second for Lollapalooza.) “Anything you take on to do, got to have a basing to to let people know what it is and what it stands for,” adds the Philosopher King of the Blues, who built his foundation in the ‘40s touring with such now-legendary icons as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Reverend Gary Davis and Muddy Waters. “You can drive a Cadillac, but if you don’t got Cadillac on it, people still don’t know what it is you’re driving.”

There’s no mistaking the imprimatur of Music Maker co-founder Mark Levinson, however, whose Cello recording equipment is recognized worldwide as an audiophile’s Ferarri. “What Tim’s uncovered is a subculture thought to have disappeared: original acoustic blues artists who have only been recorded before with lo-fi equipment” says Levinson, who re-mastered Duffy’s original recordings for the 1994 compilation A Living Past and sent him back into the field with a mobile Cello unit. And with the clock ticking on the available resource pool — Preston Fulp, pictured on A Living Past’s cover, died before its release — “it’s our last chance to hear these artists,” he adds. “High fidelity gives us the opportunity to hear what this music was, and is.”

Remarkable though they are, the recent Sony re-releases of Robert Johnson are still sealed in a time capsule of tinny 1930s acoustics, which modern ears have come to associate with the “real” sound of the blues. Duffy continues to unearth other equally noteworthy artists dating back to the ‘30s and ‘40s, who come from traditions less well-documented than Johnson’s Delta-to-Chicago line.

“In the Carolina Piedmont region, there’s a real close thread between white hillbilly music and Black blues,” notes Duffy, citing the classic conjunction of forces scholars have long credited with the birth of rock and roll. Thus Guitar Gabriel, whose blues are as deep as the Delta and as bawdy as a cathouse in heat (Jesse Helms would go ballistic over his XXX-rated “You Gotta Watch Yourself”), is equally conversant in the dueling banjos-style guitar picking perfected by Preston Fulp on the old tobacco warehouse circuit.

“The emotional impact of hearing these artists on high-fidelity is staggering,” observes Levinson, who’s not just tooting his own horn. When Gabe’s sister Lucille Lindsay starts riffin’ on the afterlife in “I’ll Fly Around Heaven All Day,” then spontaneously breaks into “Tryin’ to Make 100” on the new compilation Came So Far, you’re right there with her in her run-down nursing home, watching the Pearly Gates fly open through her old blind eyes while Gabe fingerpicks the lock off her door. When Captain Luke hisses and growls his “Dog and Cat Fight,” the fur starts flying in his Carolina kitchen. And when Willa Mae lets you know in no uncertain terms that “I’m getting old, way up in years/but I can still climb a hill/without shifting my gears,” on her slyly suggestive “Yo-Yo,” her presence is as immediate as the living room piano Michael Parrish tuned just moments before.

“If you was outside and couldn’t see it was a white boy playin’ that boogie woogie piano, you’d think it was some of the famous ones,” chuckles Willa Mae. “I’ll tell you,” adds Captain Luke, whose stunning reinvention of “Rainy Night in Georgia ” is a highlight of Came So Far, “when I was just playin’ the CD for my friends I made ‘em all be quiet. I said, listen at that piano player when he comes in!”

Parrish, for his part, never dreamed he’d be backing contemporaries of Ma Rainey and Louis Jordan in the 1990s. “What’s amazing is that this music is still around,” he marvels. “And every one of these artists is such an individual personality. Willa Mae’s an original feminist, Captain Luke’s a great folk artist who also makes these beer can sculptures. And Guitar Gabriel? The guy’s like a bottomless well of music and philosophy.”

The master of “a rendition of life” he calls the “Toot Blues” — “because you’re on the move” — Guitar Gabriel may have trouble walking these days, but he’s still taking some musical leaps at 70. In a move that may upset blues purists, the new Guitar Gabriel Volume 1 ventures well beyond drink houses into his own private Birdland, an improvisational crossroads where the starkly pre-modern meets the startlingly postmodern and the Devil’s “got his hair tied up in a ponytail to keep all the drunks confused.”

And this is as it should be. The blues isn’t a museum piece to be preserved in formaldehyde. It’s an ongoing dialogue of dynamic tensions inside a tradition that loops back to Africa — and loops forward into everything from Sun-Ra’s intergalactic explorations to P.J. Harvey’s innerspace exorcisms.

“You don’t find it in notes, it comes from the heart,” says Guitar Gabriel in his oral liner notes that give A Living Past its name. “It’s expressing about the things that you’ve been up against, what you have, what you didn’t have. Your misfortunes and your good happenings.” The $35,000 raised from CD sales to date by the Music Maker Foundation is definitely a “good happening”; Gabe and his fellow artists now have a little more than they otherwise would have had to live out their lives. But what we receive in return can’t be quantified. As Guitar Gabriel puts it: “It gives you a living past and also a future coming in.”

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.