A Tiny Town With a Global Presence

By Ryan Lee Crosby

Just off highway 49 at the south end of the Mississippi Delta, a secluded village quietly attracts passionate music lovers from every corner of the globe.

Blues fans from everywhere come to the small town of Bentonia, Mississippi (pop. 411), halfway between Jackson and Yazoo City, wanting to hear the Bentonia blues — a captivatingly ethereal and idiosyncratic blues tradition, which dates back to the early 20th century and continues to develop to this day. Mysterious and brooding, the Bentonia style is a singular sound in all of the blues. Composed of minor tonalities, hypnotic rhythms and haunting vocal lines, the music is renowned for its power to consume listeners. Nothing else sounds like it.

At the center of town, at 107 East Railroad Ave., stands a modest concrete structure which is inseparable from the music. Directly across from a set of railroad tracks, with a Mississippi Blues Trail Marker commemorating its history, the Blue Front Cafe is a living embodiment of the Bentonia blues. It’s one of the last authentic places to hear the music as it was originally played. Founded in 1948, the Blue Front, some say, is the oldest continually operating juke joint in the United States.

Owned and operated by Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, the Blue Front has been in the Holmes family since its founding. Holmes is a tradition bearer, not only as the juke’s proprietor but also as the last living bluesman from town. Holmes was initiated into music by the Bentonia blues originator Henry Stuckey, and he holds the torch as the only student of a Music Maker partner artist, the late Jack Owens, who, along with Stuckey and Nehemiah “Skip” James, made up the pioneering generation of Bentonia bluesmen in the 1920s.

At 73, Holmes remains strong and vibrant, having recently received a Grammy nomination this year for “Cypress Grove,” his 2019 album produced by the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach. In addition to succeeding Owens, Holmes keeps the music alive by hosting the annual Bentonia Blues Festival, a free five-day event started by his mother Mary in 1972. The festival is known to be the longest running annual blues event of its kind, and this year’s edition had the largest audience in its 49-year history. Holmes honors his mother’s memory by continuing to provide the entertainment at no charge, without corporate sponsorship. He presents the music on his own terms, making the fun accessible to people of all ages and backgrounds. The audience is a friendly community of people from not only the local area but also around the U.S. and beyond. Many of them have been coming for years, and the spirit of musical fellowship is strong.

Making the Pilgrimage

I drove 1,500 miles from Boston to Bentonia this year to take part not only as a performer on the festival stage but also as a member of the community and as one of the musicians Holmes mentors. The Blue Front Cafe, under Holmes’ care, is a welcoming place, with no separation between artist and audience. As a kind and generous man who is passionate about sharing the culture, Jimmy is quick to tell curious visitors about the Blue Front’s history and the Bentonia style. On any given day, you’re likely to encounter travelers who have come from great distances just to see the place and hear the music from the last homegrown artist to carry it on. In this way, the Blue Front is a kind of mecca. From the moment I first walked in, I felt I was in the presence of something sacred, something life changing. I’ve seen it happen to a number of other people since.

Over the last three years, I have traveled from Boston to Bentonia four times to learn about the nuances of the tradition, the meaning of the music and to play for audiences at the Blue Front.

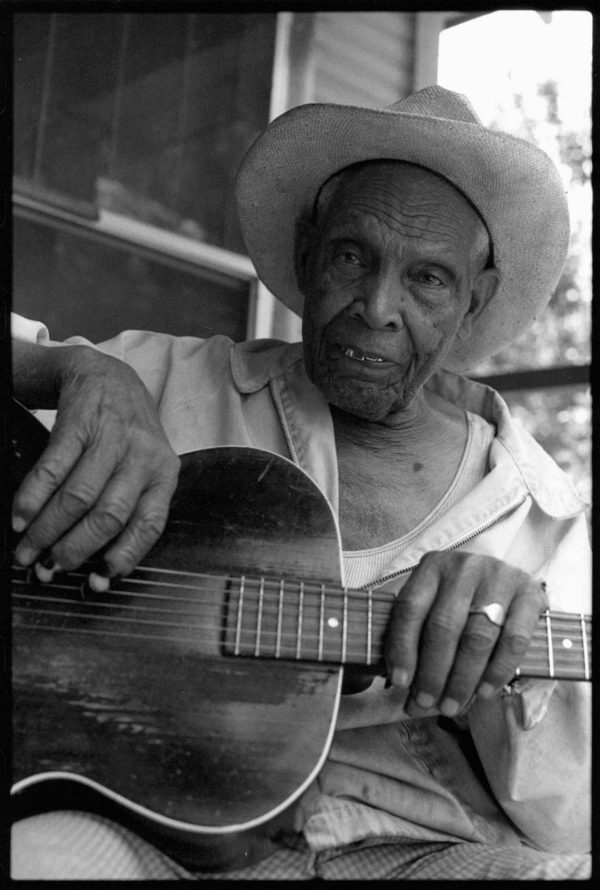

The first time I sat down for a lesson with Jimmy, he spoke of his teacher, Jack Owens, and pointed to a picture of him high on the wall, overlooking the juke.

“See that man there? He didn’t read or write music. But, he could sure play the guitar.”

The picture of Owens has stayed in my mind ever since.

Today, the image of Jack Owens hangs next to a recently discovered photo of Henry Stuckey, which was celebrated at the 2019 festival. Stuckey, who is known to be the father of the Bentonia school, took his first steps towards creating the style while serving in France during World War I. Working as a medic, Stuckey is said to have picked up a particular and obscure guitar tuning from Bahamian soldiers he was tending to. Upon returning to Bentonia, Stuckey brought the tuning with him and the Bentonia sound was born. Stuckey shared the knowledge with Jack Owens and Skip James, who later went on to become the most well known musician from the area. Local players call the tuning “crossnote,” for its ability to shift seamlessly between the major and minor. Crossnote, which is fundamentally minor, is at the core of Bentonia’s otherworldly atmosphere. The tuning is essentially an Em chord, though it is often tuned down to a full step or more.

There are no known recordings of Henry Stuckey, but listening to the albums of Jack Owens and Jimmy “Duck” Holmes in succession, alongside Skip James and the few remaining tapes of local players Cornelius Bright and Tommy Lee West, a through line begins to emerge quickly and powerfully. Jimmy learned from these musicians and is quick to pay credit, but Jack Owens holds a central role in passing the torch to Holmes, who has since added his own elements, including a pulsating rhythm that he traces to the North Mississippi Hill Country. At this year’s festival, one of the highlights was a collaborative set with Holmes and Como’s R.L. Boyce, who carries on the North Mississippi tradition set by artists like Jessie Mae Hemphill and R.L. Burnside. In trio format with Lightnin’ Malcolm adding foot drums and additional guitar, Holmes and Boyce seamlessly weaved Hill Country grooves with Bentonia melodies for a jam session that felt completely of the moment, yet also beyond time. The crowd, which seemed to feel the significance of the collaboration, was right there with them.

“If You Can Find Anyone Who Can Play This Tune, I’ll Marry My Mama”

The next day, I sat down with Jimmy at the Blue Front to ask about Jack Owens. Since his passing in 1997, Owens remains one of Mississippi’s most revered artists and a crucial link in the Bentonia lineage. His music can be appreciated as a connector between the 1931 Paramount sides of Skip James and Holmes’ 2019 Grammy nominated “Cypress Grove.” Unlike his fellow bluesman James, who sought and found wider recognition outside of Bentonia, Owens stayed close to home, where he farmed, performed at his own juke house and lived with his wife. However, just as Skip’s career was winding down in the late ‘60s, Jack, along with his partner, harmonica player Bud Spires, began recording with musicologist Dr. David Evans, resulting in the 1971 album, “It Must Have Been the Devil.” Owens, as a soloist and as a duo with Spires, also recorded for Alan Lomax later in the 1970s. The attention from these projects brought Jack many visitors in the ensuing decades and he was said to be open and friendly with those who came to hear him.

In contrast to Skip James, who was known for his delicate, spectral falsetto vocal and his ability to play piano as well as guitar, Jack’s sound was full-throated and earthy, with a commitment that was inspiring.

“Jack would play just as hard for one individual as he would for a whole stadium full,” Holmes says. “He would sit on the porch and entertain himself with his guitar and if you went there for some other reason or business, he gonna tell you, ‘Fella, let me play you a couple of notes before you leave.’ He did it for his passion. He loved playing that guitar and when he would do a song, his motto was, ‘If you find anybody that can play this tune, I’ll marry my mama.’ Because he knew it was hard to do. It was hard. Up until this day, it’s hard.”

From the early recordings through his final years, Owens’ guitar embodied the signature Bentonia elements, but his playing distinguishes itself through the use of additional tunings. According to Dr. Evans, these tunings included dropped D, standard, Spanish tuning and others of Jack’s own creation. Owens also employed chord voicings that aren’t generally heard in the songs of other Bentonia musicians. Examples of this include the 1978 Alan Lomax video for “Give Me Your Money Baby” and “My Baby’s Gone, Soon Be Gone Myself” (on Music Maker’s “Blues Sweet Blues” compilation).

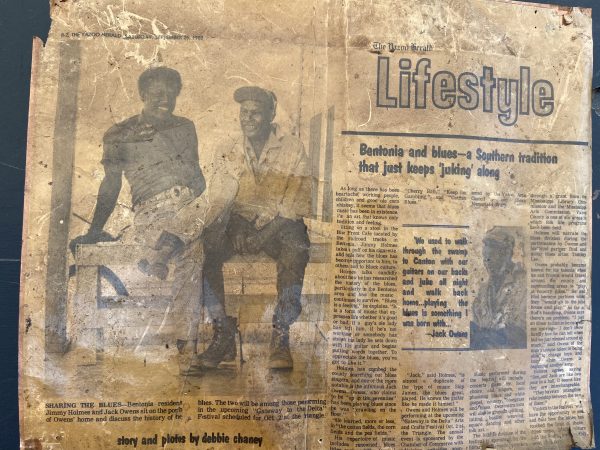

In a 1982 interview with the Yazoo Herald, Owens said he had been playing blues “since he was crawling on the floor” and that he essentially learned the music in “the cotton fields, the corn fields and the pea fields,” as well as by spending time with Henry Stuckey. Holmes recalls that Owens ran a juke house in the 1960s and played guitar there to entertain his customers. By the early ’70s, Jack started coming around the Blue Front with his guitar and over time, people stopped putting money in the jukebox and instead started listening to Owens. Holmes also started listening closely and eventually he started playing along with Jack, learning foundations of the style through classic songs like “Hard Times,” “Cherry Ball” and “It Must Have Been the Devil.”

“He wanted me to learn it,” Holmes says. “He came day after day, saying, ‘Let’s pick some.’ He said, ‘You got to learn this. I’ll tell you what to do — watch my fingers.’ I soon picked up on ‘The Devil’ and ‘Hard Times.’ It took about two months, but I could get it then, just sitting there watching him daily.”

Over time, Owens became increasingly hesitant to leave his wife Mable’s side as she dealt with illness in the last years of her life, but after Mable passed in 1990, Jack gradually began to connect with a larger audience, enjoying critical acclaim and wider exposure. In 1992, he and Bud Spires were featured in the influential documentary “Deep Blues.” Soon after, Owens received a National Heritage Fellowship Award in 1993. He also began traveling widely to perform at festivals in the U.S. and abroad.

Music Maker went to great lengths to help Owens secure a passport and booked him in Utrecht, the Netherlands, at the Blues Estafette in 1995.

“He went to Europe one time,” Holmes recalls. “I counseled him two weeks. He didn’t want to go. Finally got him to go. Got to the airport. He still was hesitant about going … and asked for a drink. Went and found him some whiskey. Jack drank maybe three quarters of that bottle … looked around and said, ‘Boy, I’ll fly this plane today!’” Jimmy laughs. “He was a character.”

Achieving Timelessness

Today, Jack’s legacy lives on in the stories of those who knew him, in his recordings and through the artistry of Jimmy “Duck” Holmes. He also lives on in the hearts of those who have made their way to Bentonia to learn about the music. At the conclusion of our conversation, Jimmy asked his brother Tip, who happened to be sitting on the Blue Front porch, to take us to where Jack used to live, a small house on the edge of town, about one mile down a dirt road off the main highway. Tip also took us to Woodbine, an antebellum home on the other side of Bentonia, where a young Skip James lived on the property with his mother, who worked there as a maid. Having the chance to see these places, as Tip told stories about the musicians, quieted my mind and opened my heart to humanity.

Part of what makes traditional music meaningful is its ability to hold the past, present and future all at once, to exist beyond space and time as a living, breathing entity. Even after the artists are physically gone, their spirits remain through what they’ve shared.

I talked to Music Maker co-founder Tim Duffy says about the Foundation’s experience with Jack Owens.

I talked to Music Maker co-founder Tim Duffy says about the Foundation’s experience with Jack Owens.

“It’s remarkable to be a bearer of culture,” Duffy says, “and of something uniquely American. And to make his home accessible to people throughout the world, to share his gift and be open with it and not slam the door on someone’s face when they come from Germany or North Carolina or Boston… and to have that open, free mentality to share the music… and now, here is this amazing legacy.

“(Jack’s) been gone for more than 20 years and his disciples are still playing his music… and it’s helped his friend get a Grammy nomination. That’s the power of being a tradition bearer. That’s the power of the roots of American music.

“People like Jack teach us how to sing. They teach us about the grooviness of minor tuning. They teach us how to be friendly and that wealth is not piles of gold, but knowledge to be shared. Wealth is being a tradition bearer of your forefathers and foremothers and making it timeless. To create art is to be timeless and Jack Owens has achieved perpetuity. How many people do that? He was an extremely special man.”

The very same can also be said about Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, who not only plays the music gifted to him by Jack Owens, but carries on the tradition of sharing that knowledge freely, in the hopes that it will continue on.

Jack Owens died in 1997, but Jimmy “Duck” Holmes can still be found at the Blue Front Cafe just about every day he isn’t on the road. He shares the authentic Bentonia blues, and visitors are always welcome. The Blue Front will celebrate its 73rd anniversary this year with two days of music on September 24 and 25. Make your plans now. It’s going to be a party.

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.