The Soulful City: The Enduring Presence of the Blues in New Orleans

BluesNew Orleans is a city steeped in music history, with jazz being the most celebrated genre. However, the blues has always been present in the city’s rich musical landscape.

Music Maker co-founder and Executive Director Tim Duffy first heard of New Orleans bluesman Little Freddie King—who at the time had scant recordings—when Duffy was in Kenya doing fieldwork. His teacher in Africa was from New Orleans and had hipped him to Freddie’s music. So, in 1991, before the founding of Music Maker, Duffy traveled to the Crescent City.

“I was staying at this place called the Maison Guest House,” recalls Tim, saying, “You could get a room for $25 a night. BJ’s was a real working-class dive. It was in the Bywater and back then New Orleans was the murder capital of the country. That was a scary place. Now, it’s hipster. I met this harmonica player who played with Freddie. I went to the roughest joint in town and there was Freddie playing. I talked to him afterwards and that started my friendship with Little Freddie King.”

It is said that New Orleans is not a blues town, not like Memphis or Chicago or St. Louis. But Tim’s thirty-plus year journey into the blues culture and players of New Orleans contradicts that assertion.

“Guitar Gabriel always told me blues was invented in New Orleans,” he attests.

Over the years, Tim’s been to many little clubs and seen some amazing blues shows, some in the Lower Ninth Ward, some with no floors, places that in many cases might have only been open for a couple of years before closing. Music Maker helped sustain one of these places, Ernie K-Doe’s Mother-In-Law Lounge, named for this 1961 regional hit single.

“The blues was always in New Orleans,” Ernie Vincent agrees.

Music Maker has made it our business to tend to the New Orleans blues roots—and support and record the musicians in the Crescent City still making music in those styles. These styles of blues haven’t been historically recorded and are as likely to be found on a front porch as in a club.

Once Freddie opened the door of New Orleans blues to Tim, the latter befriended many other artists. Tim says, “Musicians attract musicians.” He’d visit Freddie and Alabama Slim would be playing with him; Slim then introduced Tim to Guitar Lightnin’ Lee; Lee led Tim to Guitar Slim, Jr., son of the blues immortal.

“When you meet Guitar Lightnin’ Lee, Freddie, Slim, Charles Jacobs and Ernie Vincent, you feel that you’re part of a blues community. They all know each other. They’re not so isolated. They’re all part of a living, breathing culture. When you drive in a car with them, you could almost see the cultural memory that they see when they drive around town. You get a different view of the city.”

Lee concurs, saying, “New Orleans a blues town? Yes, indeed. The only place I know where you can go any time of day or night and find blues shows all over the place, I mean all night long. People don’t go to sleep. They go to sleep, another band take over. I’d pull ‘em all night, get off the bandstand, go to the barroom, get back home at three or four o’clock. I didn’t have no wife back then.”

For his part, Freddie has some caveats. “With blues in New Orleans, New Orleans is not a blues city. The blues guys and everything came from different parts of the country, the Mississippi Delta. They got down to the south and they got hooked down here and they loved the place. That’s how the blues got here in New Orleans.” His description of migration is also an encapsulation of Freddie’s own story.

Little Freddie King, born Fread Eugene Martin in 1940, grew up in McComb, MS, south of Jackson. He learned his first songs, “Baby, Please Don’t Go” and “Rascal You” from watching his father Jesse James Martin play and listening to blues on a six-watt battery-powered radio. A cousin of Lightnin’ Hopkins, Freddie made a guitar using a discarded cigar box and some hair that he plucked from a horse’s tail.

In one of Freddie’s songs, he sings about Mississippi being a place where a black man was “Born Dead.” Like many, Freddie grew up on a farm, sharecropping—and hated it. His father went to prison for bootlegging and for shooting a white man and died when Freddie was twelve. White violence towards blacks was common in McComb and blacks encountered a curfew.

A school visit to New Orleans when he was fourteen showed him a different way of life. “This is just where I need to be at. This is just the place for me,” Freddie recalls thinking. Knowing that his dad had done some “hoboing,” Freddie hopped a freight train south with little but a change of clothes.

“You gotta stop and think about it: The majority of people that was here, they was all from the countryside. They worked hard, they farmed, and they played blues on the weekend,” Ernie Vincent told New New South.

That population fostered a juke joint culture. Freddie stayed with his sister in New Orleans and soon encountered others playing blues, such as house parties at Lloyd “Curly” Givens’ home that sometimes offered fried fish, used clothing, and corn liquor. Freddie also played with street musician Jewell “Babe” Stovall, a patriarch of the scene. “That’s where the blues was when it wasn’t in the clubs. We played more there than out,” Freddie told New New South.

Adept at a wide variety of skills, Freddie got jobs hauling bananas, fixing moorings, unloading ships, and the day job he had the longest, working as a mechanic. “Freddie rebuilt distributors for these big ships in unheated shops, brutal hard work, hard labor,” says Tim.

One of the reasons many folks would move to New Orleans was that it was an economic driver. The town had been a center of shipbuilding in World War II and as a key port, day jobs were available and musicians could find fans with money to spend.

Freddie spent time at the Dew Drop Inn, a larger club and hotel that was open through the early ‘70s and would feature acts like B.B. King and Little Richard. “Once I got down to New Orleans, I learned to play much better. All the other guys, I couldn’t play like them. I tried but it didn’t work. I play my own version, what come to me, what I feel,” Freddie says. He calls his style Gutbucket Blues, also the title of a Louis Armstrong song. When asked what he means by that, he told Living Blues, “Gutbucket blues is just from the soul and the feelin’, and it’s just as deep down as you can go… The blues, what it does, is it relieves you while you’re producing it, and it makes you feel good. Still, when you finish, the same burden is right back again.”

The first electric blues album recorded in New Orleans features Freddie with Harmonica Williams and currently sells for hundreds on the collectors’ market. Because straight blues was not often recorded in the Crescent City, it is often erased from the city’s story of midcentury music.

Soon Freddie began playing what he calls “holes in the wall.” He started singing when the singer for one of his bands didn’t show up one night. Freddie played with Slim Harpo and opened for Texas blues hitmaker Freddie King, getting his artist name from the billing. One such juke joint was the Busy Bee. The first time he played there, an intense fight broke out and Freddie henceforth called it the “Bucket of Blood,” inspiring him to write a song of the same title.

Violence has long accompanied blues in New Orleans. On the Library of Congress recordings, Jelly Roll Morton told Alan Lomax, “Wherever there’s money, there’s a lot of tough people, there’s no getting around it.”

Freddie is no stranger to it. He has been stabbed; and was shot multiple times by his wife over suspicions that he was cheating. In 1989, coughing up blood and rushed to the hospital, he decided to stop drinking, a decision he’s stuck with ever since, in part to help him keep a clear head in potentially dangerous situations.

Through it all, he has found refuge in the blues, telling Gambit Weekly, of the title of his 2022 album ‘Blues Medicine,’ “I wanted everybody to know what the blues is all about, you know. It is a great dose of medicine. Once I play it, then it heals me. When I get on stage, I can be half dead when I started playing, then I’ll be a new person and feel like I’m sixteen years old.”

Music Maker has worked hard to keep Freddie’s blues medicine coming. He’s been one of the longest-standing Music Maker artists, at first with grants for prescription glasses and dental work, and then as a member of the sustenance program since the mid-‘90s.

Alabama Slim (aka Milton Frazier) will sometimes play with Freddie. Of his cousin, best friend, and musical collaborator, Little Freddie King says, “He has a different style, he plays easy, easy guitar. He’s a very, very good singer.” LFK plays the rough-and-tumble blues, whereas Slim’s style is smooth and laidback.

Slim moved to New Orleans from Huntsville, Alabama in 1965, immediately taught two cousins a few chords, and they formed a band. “’Bright Lights, Big City, things going, everybody having a good time. You could drink your little drink and walk out on the streets. I’ve been here ever since. I just heard so much about New Orleans,” he remembers. Initially, he says the trio would play “juke joints, bar rooms, you know.”

Not every New Orleans blues musician came from elsewhere.

LeRoy Williams – aka Guitar Lightnin’ Lee, says, “I do all kind of songs. I like the blues, I do old rock and roll, too. I get happy up there sometime. I do ‘Johnny B. Goode,’ Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Little Richard, Elmore James, everybody, man.” Lee has played with Al “Carnival Time” Johnson, Huey “Piano” Smith (of “Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu” fame), Fats Domino (one of Lee’s best friends), slide guitar legend Earl King, swamp-blues harp master Lazy Lester, rhythm & blues singer Ernie K-Doe, and Little Freddie King.

Born in the Tremé and raised in the Lower Ninth Ward, Lee used to go to the Drew Drop Inn, the legendary club as a teenager, saying, “[It was] nothing but musicians.” Meeting Jimmy Reed at a young age set Lee on his musical path and is the principle influence on his music. He met Little Richard there and says, “He loved New Orleans.” The Dew Drop wasn’t the only place he caught live music: “Juke joints [were] awesome, you didn’t have to pay all the time, you just went in,” he recalls.

Mentored by “Boogie” Bill Webb (who made two 45 singles and ran a drink house) and Arzo Youngblood (who himself learned from Tommy Johnson), a young Lee didn’t have too much trouble finding places to play in the neighborhood. “Me and Boogie was mostly juke joints like you know. When I got with different bands, it was different,” he says. Lee told Living Blues, “On Friday and Saturday night were the fish fries and suppers. We had that all the time. Them people would let you come up in the houses with the guitars and we’d play all up in the house…. On Saturdays, we’d all be up around Bienville Street wherever the music and suppers were goin’ on.” Other times, he would stop by Youngblood’s house, where one could expect an ongoing jam on the porch.

Even the Baton Rouge players would come to New Orleans to work, he says, remembering Slim Harpo playing regularly along the New Orleans waterfront. Lee spent time living in Los Angeles and Chicago but decided that New Orleans was where he belonged. Music Maker has helped the musician through lung cancer, from which he is now in remission.

Music Maker artists in New Orleans share a common goal: get folks onto the dancefloor.

In New Orleans, blues is often mixed with other genres of music in that pursuit. “It’s all whopped up in there together,” says Alabama Slim, continuing “Jazz, funk, and blues, you know, because you have people that listen to the blues but won’t listen to the funk or the jazz. If they would stop and think about it, with that jazz and funk, they’s playing blues licks in there.” He adds, “It is [a band town]. Solo, I don’t know, but when you get to playing with three or four, you can see the people jumping, that make me feel good when I see people move. [Dance,] that’s a big part right there.”

That’s also how Ernie Vincent found that he might have a hit on his hands back in 1972. “Every time we played the ‘Dap Walk,’ everybody jumped up and danced, you know? It was all good.”

Musicians in New Orleans take all kinds of gigs in different genres; they must be broadly proficient to stay working. When Vincent was making funk history, his horn section was made up of players who primarily played jazz; a musician in New Orleans might have a jazz gig, a funk gig, a blues gig, and an Americana gig, all in the same week. Ernie Vincent considers himself a blues musician, though, saying, “The style that I play it’s kind of different than normal blues.”

He used to host live jam sessions, where New Orleans legends such as Eddie Bo, Guitar Lightnin’ Lee, and one of his mentors, fellow Music Maker artist Ernie-K-Doe, would join him, performing at places like Mason’s Strip.

Vincent himself has played with Fats Domino. He has also backed the Dixie Cups and Frogman Henry, arranging and writing songs for the likes of New Orleans marquee names K-Doe, Alex Spearman, King Floyd, Eddie Bo, Jessie Hill, and Mardi Gras Indian bands such as the Wild Magnolias and Big Chief Monk Boudreaux’s Golden Eagles.

“The people don’t really realize that throughout my lifetime playing, it wasn’t about making the money,” he says. “It was about creating the atmosphere and creating the history… People can tell when you’re real and when you just ain’t there, you know? You got to have that feeling when you’re playing,” he says.

“People just want to dance. And my whole goal was, if you ain’t dancing, I ain’t doing something right,” insists Ernie. “That’s why everything I did almost [has] a happy feel to it, unless it’s just a slow mood song.”

The song of his that got folks moving the most, “Dap Walk,” was a long way from his start playing music living on a plantation some sixty miles outside of New Orleans. “My family, well, my dad, played a little guitar and stuff. He was a freeman, but he played guitar a little bit and he would play a little harmonica. I had about three uncles that was guitar players in Thibodaux, LA,” he remembers.

He sets the scene, saying, “When I was a youngster we used to go out there on the weekends and they would have those fish fries out there; And the first time I saw a guy playing a saw with a bow and they had the tub with the wire in it… I always wanted to play music. Took me a long time to get a guitar [though].”

Once he had one, he didn’t let it go. Arriving in New Orleans, like Freddie, he also fell under the spell of Lloyd “Curly” Givens. “He lived next door and on Friday and Saturday night they would do that moonshine party, like they did back in the day, and his wife would fry fish and they had a room in the back. They’d shoot gambling and shooting dice. That was the first time I met Little Freddie King. I met Little Johnny Taylor.”

Curly was a guitar player until he suffered an injury fixing a car, at which point Ernie could lend a hand. They would play Muddy Waters songs together. “When I went to learn this stuff, playing it, laying it down, I enjoyed it so much,” says Ernie, going on, “Curly and me, we could just play and still make people dance, just me and him. I’m on the guitar and he on the drums. And we did that. And by me learning how to play against him and timing on him.”

By the mid 1960s, he was in a band that toured every weekend, allowing its members to work day jobs.

Vincent learned to read and write music, which gave him an advantage—and helped him originate funk: he had a broad knowledge of rhythm guitar. “The majority of the guys around me, good guitar players, they could pick their ass off, but they couldn’t play no chords,” he says. He founded his own label called Kolab, producing killer funk sides for other artists like Matilda Jones. Having made music history, he still needed to work to support his family. “Music was the thing that I couldn’t stop doing,” he adds.

Born and raised uptown, Ernie spent a lot of time on Rampart Street, the center of black life and black music in the city from the turn of the century through the 1950s. “In those times, Rampart Street was a hot street… All of the Black people and Creoles and all stuff that was on Rampart Street, you know? And I grew up going up and down that street as a kid,” he says.

In his autobiography, bluesman Cousin Joe concurs, “Everybody used to hang [on] Rampart Street.” Louis Jordan namechecks the street in his 1949 hit “Saturday Night Fish Fry.” Club Downbeat featured Clarence Samuels and Roy Brown (“Good Rockin’ Tonight”)—billing themselves as the Blues Twins—in the late ‘40s, as did local favorite Joe August aka Mr. Google Eyes, aka Mr. G. Rampart’s One Stop Record Shop was a hangout for players like Professor Longhair, Eddie Bo, Dr. John, and Earl King, and fellow rhythm & blues record shop The Bop Shop was just down the block. Nearby high school McDonogh No. 35 nurtured musicians who would become part of the New Orleans rhythm & blues vanguard.

Once Rampart Street started to fade in prominence in the 1960s, music fans—initially locals, then tourists—would head to Bourbon Street. Unlike other cities, the influx of visitors has provided work for musicians night after night. “You know, New Orleans has been a place where people can get pretty regular gigs, because music is so much a part of the town,” says Vincent.

Take Charles Jacobs, who played Bourbon Street six or seven nights a week for some twenty-five years. “I upset Bourbon Street. I ought to do a song about it. I changed it pretty much,” the bluesman exclaims, saying that he wouldn’t play a different set for tourists than he would play for New Orleanians. “If I do a song by any other, I’m going to do it, but I’m going to do it my way. I feel it and I go with my feelings,” he adds. Remarkably, he did this all while working driving a truck for a glass factory five days a week.

“I was from the farm. Living on the farm with my grandfather, I had to work in the field. They trained me how to do this and do that, plowing and all that stuff. I always could sing,” he recollects. He started playing guitar for a gospel group and in church. His mother lived in the Crescent City, so he saw an alternative to rural life of Prentiss, MS, and he departed after graduating high school. Once he got to New Orleans, he says, “Other guitar players would be in the neighborhood and show me a lot of things and sit on the steps.”

One of those musicians was Little Freddie King, whose band he joined as a singer and who would show him licks on the guitar. “We just [had a] music bond, all day, as much as we could. At night, we was rehearsing and jamming. We’d have street blocked up.”

The group would venture out to “play rough joints.” He remembers a night where he had to intimidate an armed and rowdy patron. Even though he wasn’t carrying any weapons, Charles told him, “Ain’t nobody gonna fuck with Charles!” The other guy backed down.

He would steal gigs from other musicians. “I believe in testing my talent. Let’s go around and see where the guys are working and take his job. So I sit in. Sure enough, they all come to me and they want to holler at me. [In one instance,] the place was like a honky tonk, wide tables and everything. Friend of mine came to me and said take it and put it on the map, make all kind of people come see you, people come from all over the place. Midget bar they call it, uptown neighborhood on 3rd and LaSalle street.”

Between the intense competition and the musical eclecticism, the standard of musicianship in New Orleans is very high.

Jacobs soon graduated from barrooms to clubs. He recalls a successful residency with his band, replete with a horn section, at the Horseshoe Club in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. “The entertainers and musicians here, they highly respect me,” he declares.

One reason he was recognized is his wild sense of style. At the Horseshoe, he went all out. “I had named my band Charles Dickens and the Wagon Train at one time. That was in the ‘70s. [When we would] take a break I would say, ‘Wagon ho, dismount.’ We was wearing cowboy hats, fringe jackets and stuff like that. It caught on,” he says, continuing, “I always make sure I looked good and everything. People wonder what I did because as an entertainer, I want to look like one.”

These artists are carrying on a musical lineage whose seeds were planted centuries ago. Baton Rouge blues musician and scholar Chris Thomas King has made a compelling argument in his book Blues: The Authentic Narrative of My Music and Culture that not only is New Orleans a blues town, but that the blues was a New Orleans creation, a modernist movement seeking freedom of expression and a cultural assertion against the city’s “blue laws” meant to curb Creole culture. By its nature, it resists the prevailing music of the time, departing from the western scale. “Blues” is a Louisiana Creole word that’s derived from the phrase “sacré dieu.”

King traces the origins of the blues to formative New Orleans and before. A subset of New Orleanians can trace their heritage back to Egypt, where the clarinet, piano, and trumpet were invented; free blacks were in New Orleans as early as 1513; guitars were known to be in Congo Square by the 1700s, traveling with the Moors as well as people from Senegal and Mali. “Father of the Blues” W.C. Handy lived there in 1896-97. The first blues published came out in 1908 from Algiers, New Orleans. Almost every hit blues song of the 1920s can be traced back to New Orleans. King Oliver would ask his band members for blues compositions. Train pullmen based in New Orleans would sell blues records along their routes north.

Jelly Roll Morton (born as Ferdinand LaMothe) calls “Make Me Down a Pallet On Your Floor” “one of the early blues that was in New Orleans many years before I was born.” Morton calls blues joints honky tonks “where only the blues was played,” citing favorite players like Tony Jackson that could draw a crowd in the 1890s. “Well, the girls would start with ‘Play me something there, boy, play me some blues,’” Morton said.

Morton and Bunk Johnson both cite New Orleans piano player Marie Desdunes as the earliest known blues composer. “The girls was crazy about this little blues… Here was among the first blues that I’ve ever heard, happened to be a woman, that lived next door to my godmother’s, in the Garden District,” Morton told the Library of Congress.

Morton attributes “one of the earliest blues” to Buddy Bolden, telling the Library of Congress, “We used to play the barrelhouse blues, that old blues… Bolden, he’s the one… barrelhouse blues, that’s what they used to call it.” Bolden—and later Morton himself—

performed on trains, spreading the music from New Orleans. According to trombonist Bill Matthews, who saw him play, Bolden would play “old slow lowdown blues.”

When Creole musicians would play with black musicians, the style would morph a little. Morton attested to the Library, “You have to play real hard when you play for negroes, you understand, and when you play with negroes. You got to play hard. You got to go some, the twelve-bar… they play like they’re killing themselves.”

Morton was also a subject of the formative blues myth that he sold his soul to be able to play, decades before the same was said of Robert Johnson.

Over time, like Freddie and Alabama Slim, prominent blues musicians began to converge on New Orleans, including Ray Charles (for a time in the 1950s), Papa Lightfoot, and Roosevelt Sykes.

By the 1950s, New Orleans rhythm and blues was heard on recordings around the world, many tracks laid down in Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Recording Studios and then Cosimo Recording Studios. Those rooms and others pumped out numerous hits for labels like Specialty and Imperial, featuring musicians like drummer Earl Palmer and Dave Bartholomew, who would also perform at the Caledonia Inn. Guitar Lightnin’ Lee talks about catching concerts at another spot, saying, “I used to sneak up at the Dew Drop Inn.”

The recent historical turning point in New Orleans musical history is Hurricane Katrina. Though the storm scattered the blues community, some temporarily and some permanently, the scene persists. Living Blues said, “Despite this attention, many artists who performed more traditional forms of blues have continued to remain largely off the radar for tourists or even New Orleans music aficionados. As the interviews here with King, Guitar Lightnin’ Lee, and Brother Tyrone suggest, blues has had a strong presence at small clubs featuring live music.”

In the storm, Ernie Vincent lost his studio. Little Freddie King and Alabama Slim spent a year in Texas. Charles Jacobs, who sang six nights a week, stopped gigging after Katrina. Gentrification since the storm presents a challenge to musicians.

Alabama Slim chronicles his Katrina experiences with his wife Dixie and Little Freddie King in his song “The Mighty Flood.” Slim’s wife Dixie worked at the Monteleone Hotel (on higher ground than much of the city), which set aside a room for her during Katrina. Slim sings the story:

“They called for everyone to evacuate

It was very cloudy and getting late

I called Little Freddie king

I told him to come on by me

He’s my very, very best friend

The city had out a curfew

No one on the street after 6pm

I told little Freddie king

He had fifteen minutes to make it here

And he was there in ten

Me and my wife was held up at the Monteleone hotel

Oh yes, no doubt in my mind it was going to be hell…

The mighty flood that happened in New Orleans will always be on my mind.”

In the wake of Katrina, Music Maker has stepped in to help, granting Freddie a Gibson B.B. King model “Lucille” guitar.

Of Music Maker’s assistance, Vincent says, “But, it’s not so much about the money. It’s the help that they do. I appreciate it. And I know they they good for Lightnin’. And they do good for a lot of musicians, you know? And I’ve been out there playing, you know?”

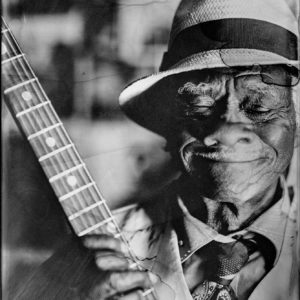

New Orleans has always been a city that embraces folks who don’t feel like they fit in elsewhere, and sometimes musicians will talk about how, rather than choosing to live in New Orleans, it chose them. In recent times, the city has attracted new blues voices like Washboard Chaz, Europe’s Ghalia Volt, and Music Maker artist Slewfoot to move to town. The Crescent City Blues Festival, featuring performers like Brother Tyrone and the Mindbenders, supports the scene while WWOZ regularly airs blues music. It’s also a place where art and music intersect. New Orleans Museum of Art hosted an exhibit of Tim Duffy’s tintype photography and the large prints of his photographs hung in public locations for years.

Supporting these and other culture-bearers is a task to which Music Maker is dedicated and uniquely suited.

Vincent concludes, “I feel like what we do and the type of stuff we do, that’ll never die… And I think right now, ain’t any but a few of us old timers left, and it’s time for us to get on back to kicking it.”

By Nick Loss-Eaton.

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.