Finding the Roots

BluesMusic Maker Foundation’s job is to tend the roots of American music. Music lovers think we already know the pathways those roots follow. But our vision is too narrow. It’s time to broaden our view.

By Chuck Reece

The blues belong to Mississippi. Everybody knows that, right? That’s true, kind of. It’s correct, but not entirely. Jazz belongs to New Orleans. Everybody knows that, right? That’s true, kind of. It’s correct, but not entirely. And to keep hewing to that story does the more complicated one a disservice.

~~~

Few people in America have spent more time preserving threatened forms of American music than Tim and Denise Duffy, co-founders of Music Maker Foundation.

But even adepts like the Duffys can still have their musical psychogeography reconfigured. Especially when it’s Archie Shepp doing the reconfiguring. In an on-stage interview at 2018’s New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, they heard Shepp challenge the standard mythos of jazz’s origin story.

Tim remembers it this way: “He said, to all these New Orleans devotees, ‘You think jazz was invented here, but you guys are wrong. All African American music started when all the slaves were brought into the East Coast, and we formed the first African American musical traditions. And then when we were sold down the river, to clean up the swamp, we brought a lot of our music with us down here.’

“So,” Tim concludes, “that made me think.”

And for the last several years, Music Maker has been uncovering and documenting a rich, multigenerational tradition of Black gospel quartet music—“jubilee music,” as one of its practitioners, Bishop Albert Harrison, declares—in eastern North Carolina. That, Tim believes, “is arguably one of the greatest Pan-African musical communities in the world, with this gospel quartet tradition that holds remnants of slave hollers, work songs, and all the essentials.”

The eastern seaboard, not Mississippi, not New Orleans – how this gospel tradition arose and endured in the farm country of eastern Carolina didn’t fit well into the two big origin narratives of American music. Those boilerplated stories were just too simple.

Thinking back on the root-chasing rambles of Music Maker’s past quarter century, Duffy already had plenty of intimations of what Shepp’s words had synthesized. Duffy’s first ramble began in the late 1980s. That was when James “Guitar Slim” Stephens (the blues player whose work Duffy documented as a graduate student in the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s Folklore program) told Duffy that to understand the blues, he had to find Guitar Gabriel. Gabriel was an obscure guitar player who lived somewhere around Winston-Salem. And when Duffy finally found Gabriel in 1991, it opened the doors to a whole world of players. These were people upholding the Piedmont blues tradition—a style that sounded quite different from the Delta blues.

“The Piedmont blues is a fancy way of picking,” says Music Maker partner artist Shelton Powe, a keeper of the Piedmont tradition. “It’s a combination with bluegrass, with some jelly put on it. It’s a little bit different than other forms of blues, say, Delta. The Delta’s more a haunting sound, deep down. Piedmont’s like a happy, ragtime deal.”

That Powe hears some bluegrass in the Piedmont blues is telling. It suggests the Piedmont blues arose where the string-band music of white Appalachian settlers and the blues music of African Americans intersected. It happened when musicians happened to cross paths.

Think about the hoariest legend in the blues mythos: Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads. The high drama of the tale has obscured its down-to-earth origins at a literal crossroads, where Highway 61 meets Highway 49. Musical magic occurs when people of different cultures, carrying different instruments, intersect. Musical evolution can only begin at the crossroads.

After three decades of rambling, Music Maker’s founders are now asking themselves a daunting question: Where does American music really come from? This story presents an answer to that question. But it will draw your attention not to endpoints like the Mississippi Delta and New Orleans. Instead, it will guide you through intersections, spaces and times where musical people happened upon one another.

Will this story be correct? Will its answers be complete?

Yes. But not entirely.

~~~

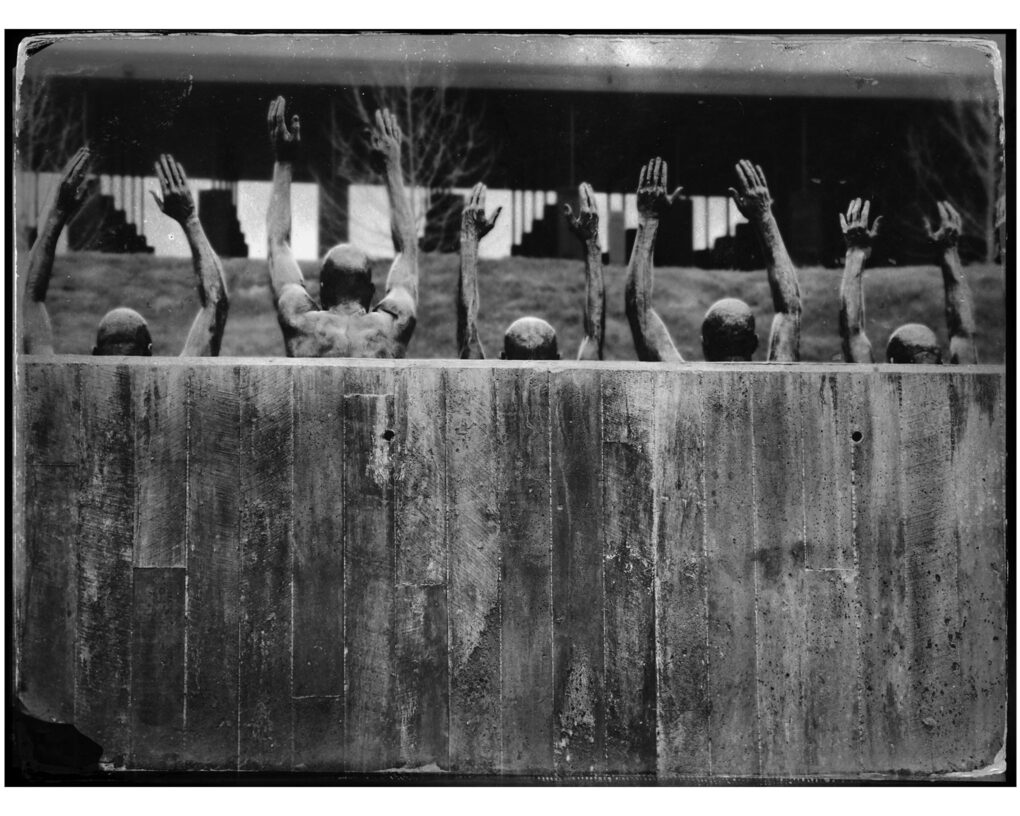

But we can’t just focus on America’s musical intersections. If we do, we exclude the harsher political and economic realities of a nation built on chattel slavery. Not all intersections are safe, and deals made at crossroads are rarely fair. So to explore the intersections where American music began, let’s take a quick trip to Montgomery, Alabama and that city’s Legacy Museum. The museum opened five years ago to tell a more complete story of American history, as their tagline promises, “from enslavement to mass incarceration.”

On entry, every visitor to the Legacy Museum is immediately confronted by a set of world maps. On these animated maps, one sees a series of black dots begin to travel from West Africa to the Americas. Each dot represents a ship jammed with kidnapped Africans, brought in chains as slaves. The first ships sailed in the mid-1500s, and landed both in the Caribbean and on the eastern coast of South America (primarily Brazil). In 1619, the first ships reached North America, landing at Jamestown (population 700) in the Virginia colony. As the years pass on the map, the pace of enslavement speeds up dramatically. Ships swarm the North American shores, first up north, and then, overwhelmingly, south of Jamestown.

This process continued for two more centuries until the United States government banned the importation of slaves in 1807. But at that point, the nation already had 4 million enslaved black people. Or, as the ruthless metrics of the South’s slave traders would have it, a self-sustaining population of 4 million pieces of human chattel.

As the dots on the Legacy Museum map proliferate, it gets easy to lose track of each individual point. Locking back into the particular, we remember that each dot represents a real slave ship. But each slave ship itself carried a double cargo: a boatload of evidence of American inhumanity, and a boatload of human beings integral to the creation of the American music loved the globe round.

In the early days of the North American slave trade, enslaved Africans and their European “masters” interacted little musically. From the outset, the slavers set about stripping away all cultural traditions and beliefs from those they had abducted. Of course, such a horrid aim could never be fully achieved. But over the decades, many enslaved Africans did increasingly adopt Christianity.

“The church figures largely in the creation of American music,” Music Maker co-founder Denise Duffy says. “Church was the only place African Americans were allowed to assemble and have a voice.”

All musicologists trace the roots of both blues and jazz back to the church, where African rhythms first intersected with stories of salvation and retribution in the Old Testament. From the Black church, the story goes, African American music traveled outward and crossed paths with the Scots-Irish tunes that came to the U.S. with European colonists. But it is easy—too easy—to limit the exploration of American music to the intersections of Black music and white music.

For 20,000 years before Columbus, indigenous peoples lived and died on the North American continent. This is by now a well-acknowledged fact, if not always one kept in mind. But what about their music?

~~~

This is where Malinda Maynor Lowery has a story to tell about that. Lowery is the Cahoon Family Professor of American History at Atlanta’s Emory University, and the former director of the Center for the Study of the American South at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her roots are in Robeson County, North Carolina. Robeson County has for centuries been home to the Lumbee tribe. Today with over 50,000 members, the tribe is the largest east of the Mississippi River still lacking official recognition from the Federal Government.

Lowery’s Lumbee, and throughout her career has charted the contributions of her people to American culture. She thought and written extensively about how the history of the slave trade — and its collision with the culture of Native American tribes — crucially shaped American culture.

“The really concrete example for me is the landing of a Spanish ship that left Hispaniola with African slaves and some Spanish colonists intending to set up shop in what became South Carolina,” she says. “This is in 1524, so way before The Lost Colony. And because it’s the Spanish, not the British, it’s been left out of the story of American history. But when these colonists arrived, the African people they brought here in chains mutinied. And many of them mutinied by running to live with Native communities that were very much present in that area of South Carolina. The only reason the Spanish went there was to try to exploit the Native people who were there, to enslave Native people, as well as to continue the enslavement of the African people they had captured. And so that mutiny took the form of running away, but it also took the form of African and Native people joining together to dismantle this emerging colony. And what songs were created out of that moment? How did these people learn from one another if not by music, if not by using their innate tools?”

This was four centuries before the advent of sound recording, so we will never hear the songs Lowry asks us to imagine – they represent a present absence. But the implication is clear: music was central to how enslaved Africans and Native Americans learned to communicate with each other.

Europeans who wanted to build an economy in North America on the cheap, by enslaving and exploiting people who did not look like them, could do exactly that—and America is still reckoning with the aftermath of those Europeans’ original sin. But from the forced integration of cultures came music and other art forms that still, every minute of every day, thrill people all over the world.

“The oppression that went into that, the violation of sovereignty and human rights, and the violence that went into the creation of the United States can’t undo the periods or the moments of sheer possibility created by African and Native American people,” Lowery concludes. “And we’re still experiencing that sheer possibility.”

Lowery emphasizes that the true roots of American music reach back far beyond the establishment of the United States in 1776, beyond the beginning of the North American slave trade in 1619 (or 1524, as she notes), and even beyond Christopher Columbus’s “discovery” of America in 1492.

“Thousands of years of cultural development took place leading up to 1492,” she says. “And because there were no Europeans here to write down what they heard, I think sometimes historians or even more casual observers get lost in that. It’s like the ‘if a tree fell in the forest’ question. Yes, scientifically, the tree makes a sound. It must make a sound. And furthermore, there are also animals and plants that are there to hear the sound. It doesn’t require white people to note that something is happening in order for us to understand that music was here, culture was here — in every way, shape and form of people creating something, creativity was here. And so the rabbit holes I go down are the same ones you’re asking about: how regionally specific can we get with what was developing there? Because again, just by virtue of what was available in the way of methods of making music, that’s going to vary from place to place. What gets popular, what becomes popularized, what people pick up on and run with, that’s creativity, that’s music. And that’s going to vary from place to place and population to population.”

~~~

Glenn Hinson believes that if you want to understand what happens at musical crossroads, you must look at the instruments that converge at those intersections. He also believes you must understand what circumstances music makers are in when they arrive at their crossroads. And finally, he believes you must understand the purpose behind the music people make, what drives their desire to create.

Hinson is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s Department of American Studies, who for over forty years has studied folklore, ethnography and what he calls “African American expressive culture.”

“If I were to look at the roots of Black American music along the Eastern seaboard, I would begin with the realms of rhythm and song and wordsmithing,” Hinson begins. “In so many areas along the Eastern seaboard, enslaved Africans were denied the ability to re-create and perform with their musical instruments. So while there were attempts to re-craft in many areas the musical instruments of West Africa, both the stringed instruments and the drums and the varieties thereof, early Black codes across the South restricted that music making dramatically.”

Slave owners denied the Africans they had enslaved their native instruments, fearing that music itself could be a means of communication. If the drum beats of slaves could signal a coming escape attempt, then the slave owners resolved to confiscate and destroy the drums. The restrictions they imposed, Hinson argues, resulted in enslaved Africans developing music that was “radically different from early white American music.”

From that era of restrictions, he says, we must “look at where those songs started or what sort of settings there were in. There were songs of worship, songs of work—lots of songs of work—songs of comfort, and songs of play. So that you had worlds of West African song that provided both connection and comfort on these shores.”

Oddly enough, the restrictions white planters put on the music their Black slaves could make fell away as the planters began to see that music as entertaining. Let the slaves play at the parties, and it’ll entertain all our friends, right? Then, in the wake of the Civil War and the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude…shall exist within the United States,” more and more musical intersections happened.

By now, it should be clear to you that the richness of American music did not originate in the Mississippi Delta or in New Orleans. From the time of the mutiny Lowery describes, it would be another two centuries before the city of New Orleans was even founded — and two centuries before European settlers first came to the Delta to fell the forests and plant their crops.

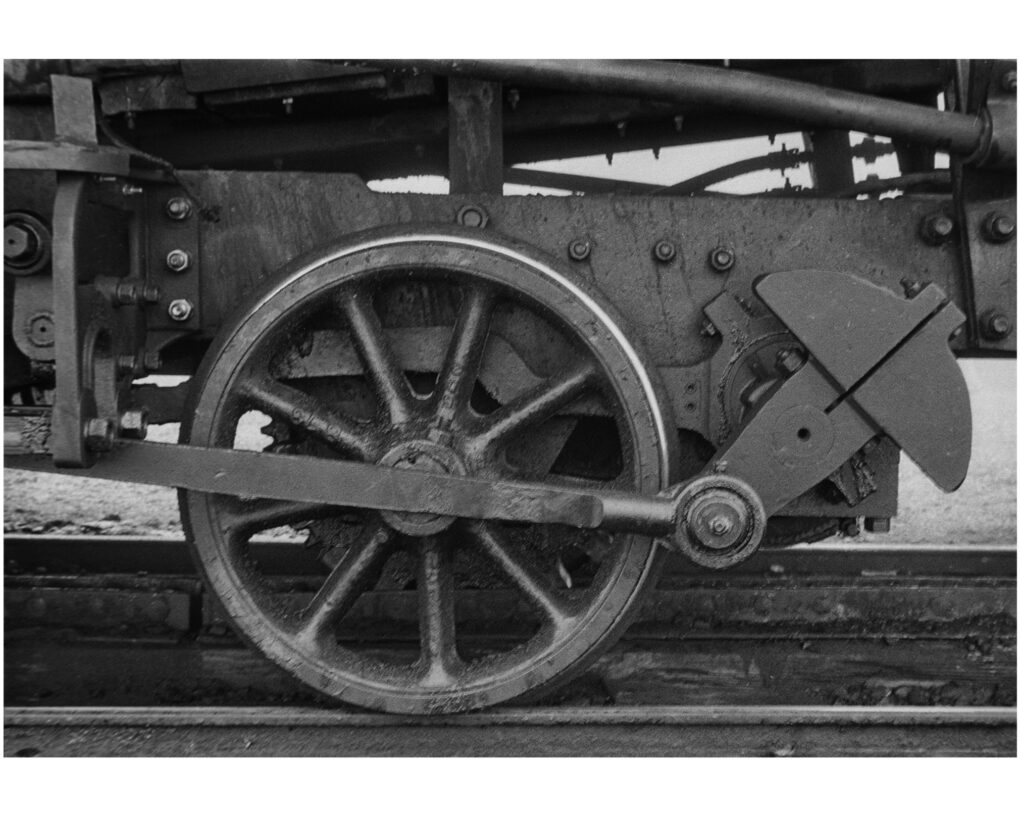

The first intersections that gave birth to Southern culture and music clearly occurred along the Eastern Seaboard—because that’s where the people were, the Indigenous, the African, and the European. As those people traveled more widely by foot, on horseback, or on boats, more intersections were created. But the creation was greatly accelerated in the late 1700s, fueled by two huge innovations: Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793 and the building of the United States’ first steam-powered railroad in 1827.

~~~

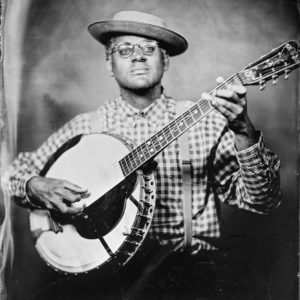

This is a great place to bring the “American Songster,” Dom Flemons, into this discussion. Flemons, for the uninitiated, was a founding member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, who won a Grammy Award when they shook up the music world by reviving the lost sounds of African American string-band music. From that launching point, Flemons became one of our foremost experts on American songs and the history of their origination.

Flemons consistently comes back to the idea that if you want to follow musical roots and find the intersections of cultures, you must follow economic activity, the migration of people who follow that activity, and changes in people’s modes of travel. When Whitney made it possible to process cotton mechanically on a huge scale, planters rushed to clear forested wetlands, like the Mississippi Delta, so more cotton could be planted. And they rushed to build river ports to transport that cotton to gins for processing.

In the Mississippi Delta, Flemons says, “they clear the land out in around the 1830s, because that was when they actually had removed the Native tribes, and then you start to have actual settlements and then cities. So you’re talking about the 1840s before the Mississippi Delta really becomes a factor in the grand scheme of things.”

The railroads created the opportunity for the number of musical intersections to expand exponentially, Flemons says. Imagine our nation limited only to travel by foot, horse or boat. The distances people could cover by the first two were limited, and boats, of course, could travel only on water — around the coast or into the interior along rivers. That leaves us with relatively few points of intersection for travelers. Then the trains come along, with countless depots built at stopping points, each of them an intersection where travelers could meet each other.

“So then the train becomes an important part of music like the blues because the train is what really sets people on an inward path,” Flemons says. “They had something beyond the Mississippi River to take them up and down and all around.”

And large-scale agricultural industries, he said, made it easier for people of different races and cultures to cross paths.

“I’m not saying there wasn’t segregation in North Carolina, but in the cotton mills and in the tobacco farms, there are these very deep-rooted cultures that allow for musical exchange to happen very different from other places,” Flemons says. Work brought Americans of all backgrounds together as they brought cotton and tobacco to common marketplaces.

“One thing that was definitely key to Piedmont blues was tobacco,” says Dolphus Ramseur, who manages the Avett Brothers and Amythyst Kiah and who has studied the music of North Carolina throughout his entire career. “All of the blues musicians would follow the tobacco circuit from Wadesboro to Durham and Winston-Salem. And on payday, they all would be sitting out, playing on the street corners right outside the facility where people were paid.”

Wayne Martin, the executive director of the North Carolina Arts Foundation, who has studied the state’s traditional music for forty years, believes the same holds true for string-band music, particularly forms in which the banjo—an African instrument—is critical.

“Things hop around and come back in ways that are hard to describe,” he says. “I can’t draw a straight line back from Ralph Stanley to African American string bands. By the time Ralph Stanley was growing up, for all I know, the people in the county where he’d grown up may have forced all the people of color out, because that happened a lot. Ralph Stanley may have not grown up with very many people of color around him. And he learned the clawhammer style (of banjo playing) from his mother. Ralph Stanley and Earl Scruggs may never have known any Black banjo players. You can see how they wouldn’t have. But that doesn’t mean, if you look at the history of the banjo, it doesn’t lead back. It does lead back.”

~~~

Ultimately, the lesson is this: don’t focus on final destinations like Clarksdale, Mississippi, or New Orleans, or Nashville. Instead, look for the intersections—the boat landings, the train depots, and the crossroads. Anywhere people of different backgrounds and cultures and colors, with music in their hearts and instruments to play, cross paths and learn from each other. They meet, explore, then travel onward, to the next crossroads, bringing what they learned with them.

From the earliest days when African and Native and European cultures met, whether by force or by accident or by choice, new music blossomed. The path of their travels began along the Atlantic shores, but over time, their travels led to thousands of destinations.

Chasing the roots of American music will never lead you to a single place. It will lead you to thousands of places. And Music Maker’s job is to travel as many of those roads as they can, to find as many intersections as their resources allow, to uncover, support and preserve the music that happens where any two musicians meet.

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.