Discover the Sacred Soul of North Carolina

SacredThe jubilee quartet style has roots going back to the 17th century — and branches into life in the 21st. This music influenced the formation of rock ’n’ roll, soul, and rhythm & blues.

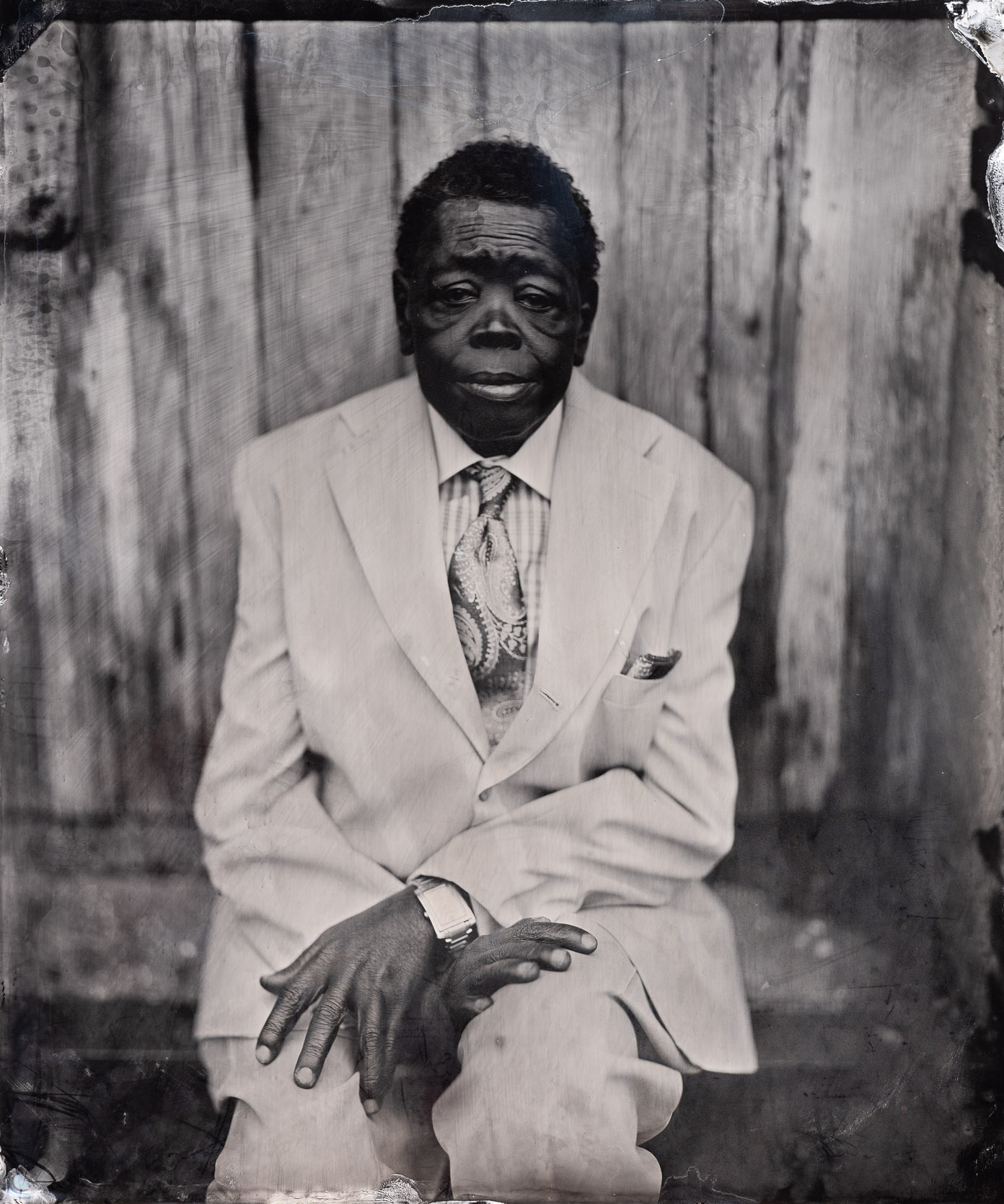

Photo by Zoe van Buren.

“Pillar of Hope”

“Eastern North Carolina, it’s a musical area,” says Anthony “Amp” Daniels, leader of the Dedicated Men of Zion. “When I think about it, it’s just overwhelming to think about all of the different talents.”

Daniels himself is an embodiment of this musical abundance. He learned gospel music from his parents, who learned it from their parents. Now, his children are great gospel musicians. Brothers, sisters, aunts, cousins, and many friends are musical as well. Follow all these lineages and a dense web of musical connection emerges. It’s like a thick forest with unbelievably deep, intertwined roots; and above the surface new limbs sprout perpetually. DMZ’s four singers — Anthony Daniels, Antoine Daniels, Marcus Sugg, and Dexter Weaver — are all related by blood or marriage.

“In Eastern North Carolina it seems like there are a lot of quartet groups, a lot of really soulful singing,” Amp says. “It’s just people who are very serious about what they are doing and you can tell it through the songs and the way that they deliver.”

Styles flourish in Eastern North Carolina that singers in other areas have abandoned as too old-fashioned. It’s not that musicians in this area aren’t conversant in the full range of contemporary sacred music — from inspirational R&B and holy hip-hop to slick Nashville-produced praise music — it’s just that they still find power and vitality in the music their elders taught them.

Faith and Harmony is another family group carrying on this sacred soul tradition — two sets of three sisters who are first cousins who grew up singing together in Greenville, North Carolina. One of its members, Ke’Amber Daniels, believes the tradition persists because of the critical role Black churches have always played in these rural communities.

“In the rural south, I feel like the black church was their pillar of hope,” she says. “It’s where they went to pray together, to sing together. If someone was going through something, that’s where you find your support. You get your guidance there.”

Enslaved people lived in Eastern North Carolina by the late 1600s. The families of many pre-Revolutionary War arrivals never left the area. It’s not hard to find Eastern North Carolinians today — white and Black — who still live within a 40-mile radius of the land where their ancestors lived and worked 300 years ago. Put that in relation to the fact that gospel singing is so often passed down through families, and you realize just how far down the musical roots of this area go.

“There Ain’t Nothing Like This Old Jubilee Gospel Quartet Singing”

Family also is how Johnny Ray Daniels, Amp’s father, got his start. “Growing up here and being home, my mother used to make us sing and when people come [over], she would say, ‘My boy can sing,’” Daniels says. He made records with a rock and R&B group called the Soul Twisters before devoting himself fully to gospel in the 1960s.

“In the eastern part of North Carolina, there ain’t nothing like this old jubilee gospel quartet singing,” says Bishop Albert Harrison, whose group the Gospel Tones works out of Ahoskie, North Carolina. Bishop Harrison originally hails from the experimental planned black community of Soul City in Warren County.

“I love it all, but you give me that old jubilee gospel singing and we can get through,” Harrison says. “Through brick walls. With the help of God. We can go through steel walls. That word, the way you sing it from your heart, it penetrates.”

From Carolina to Carnegie Hall

The area’s distinctive gospel style first came to national attention in the 1930s with a Kinston, North Carolina, group, Mitchell’s Christian Singers. The quartet’s tonal heterogeneity and unadorned harmonic palette made their a capella style something of a relic even for the time. But music industry legend John Hammond reported that both he and Goddard Lieberson — future president of Columbia Records — wept uncontrollably when they first heard the group. At the behest of Hammond — whose patronage and advocacy fueled the careers of some of the most legendary figures in American music, from Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Billie Holiday to Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen — Mitchell’s Christian Singers traveled from Kinston to New York City to sing in 1938’s landmark “From Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall.

After World War II, Mitchell’s Christian Singers’ folk style of quartet gospel evolved into a style that formed the basis for the most influential American popular music genres of the 20th century. With new arrangements, electric instruments, and a performance style that prized ever-increasing climbs in intensity leading to explosions of collective ecstasy, gospel quartets laid the foundation for both soul music and rock ’n’ roll. Ray Charles, Little Richard, Sam Cooke, Wilson Pickett, James Brown — none of these artists would have happened without the precedent of post-WWII gospel quartets. “Mainstream American music, a lot of it has stemmed from the church,” says Ke’Amber.

In the 1950s and ’60s, black churchgoers in Eastern North Carolina denounced rock and soul while fervently embracing the hard-driving quartet style that was their sacred progenitor. This was a time of raging white supremacy in North Carolina. As the Civil Rights Movement took hold nationally, a fiery countermovement emerged in North Carolina, whose Ku Klux Klan membership swelled to the largest in the country. Pitt County — home to many of Eastern North Carolina’s sacred soul artists — was one of the state’s most active Klan counties. The driving quartet singing that rocked churches, community gatherings and record players filled folks with the joy, hope and strength to fearlessly face the “many dangers, toils and snares” that surrounded them.

“Going Up The Rough Side of The Mountain”

It is perhaps because this music was such a powerful agent in helping Black Eastern North Carolinians get through this dark chapter that the quartet gospel style has remained vital in the region. But remaining vital does not mean staying stagnant. Grooves and riffs from the secular styles derived from quartet gospel have been mixed back in. At the same time, some singers employ phrases and mannerisms that reach back to the folk gospel era of the early 20th century and even earlier. Groups also take inspiration from gospel choirs and the ever changing trends in contemporary pop gospel. All of it amounts to a vibrant sacred soul tradition.

You can hear one manifestation of this sacred soul tradition in the supremely funky 1970s records made by the Glorifying Vines Sisters of Farmville, North Carolina. Alice Vines explains the lineage.

“It first starts from church, right,” she says. “So you start from church and you start singing and sometimes people say, ‘Hey let’s form a group.’ So when you form this group, probably your parents did this. So then they start dying off, one in the family starts taking the other one’s place, the younger ones taking the older’s places. So they’re still carrying on the tradition that the older folks carried on.” The Glorifying Vines Sisters have over four decades of performing experience and have shared the stage with some of the biggest names in the genre, including the Mighty Clouds of Joy and the Swanee Quintet.

The 1984 smash sensation by Rocky Mount’s Rev. F.C. Barnes, “Going Up the Rough Side of the Mountain” can also be traced back to North Carolina. Like Mitchell’s Christian Singers in the 1930s, this song sounded old-fashioned even for its time. But it proclaimed spiritual truth with such undeniable power that gospel fans couldn’t resist. F.C.’s son, Luther Barnes, has followed in his father’s footsteps, building a long and successful career with his own take on roots-infused Eastern North Carolina sacred soul. Mentored by Barnes, the Johnsonaires debuted in 2000 and have been singing in their hometown of Greenville, North Carolina, and on the road ever since.

Other key figures with deep roots in the area with include Blind Butch, who blossomed into a musician in the 1950s and ’60s at the segregated North Carolina School for the Blind in Raleigh, listening to both gospel and, illicitly, rhythm & blues records. Little Willie and the Fantastic Spiritualaires was a brother band that had been singing for over 50 years until Little Willie’s passing in 2021.

Other styles further away from quartet singing also mark the region. An hour north of Greenville, Bishop Dready Manning played harmonica on a rack with his guitar and his wife Marie singing with him, drawing heavily from a blues sound. Like many sacred soul artists, he got his start as a heavy-drinking bluesman before disavowing it in favor of the Lord. Manning says he had a “converted mind.”

“The Lord gave me this way of playing,” he explains in his velvety voice, “and He told me to use it in his service. So that’s just what I’m doing.” After surviving a hemorrhage at 28, he became bishop of the St. Mark Holiness Church in Roanoke Rapids, N,C. Manning’s family was a big part of his musical life: He and Marie and their five children toured for years and produced numerous 45s, albums, tapes and CDs, in addition to singing together in church every Sunday. His church services were rebroadcast on both radio and cable TV locally.

The Branchettes of Johnston County, North Carolina, first met as part of the Long Branch Disciple Church’s senior choir, whose style pulled from the African American traditions of congregational hymn singing. Ethel Elliott passed away in 2004, but Lena Mae Perry and pianist Wilbur Tharpe continued to perform together until Tharpe’s passing in 2021. They would often make two or three performances at different churches each weekend.

Living Roots

When Anthony “Amp” Daniels reflects on the sacred soul style of Eastern North Carolina, he says, “It all comes from the same root, but it’s like a tree and branches out. But the roots, that’s where it all came from.” The metaphor of roots gets used so often in connection to music that people sometimes forget that roots aren’t simply stuck in the past. Roots are alive. Although they reach deep down into the past, they nurture life in the present.

“When you sing it the old way,” Lena Mae Perry of the Branchettes said, “you’re really meaning what you’re talking about.”

The roots of this music feed the sacred soul traditions of today — traditions alive with the same power to stoke Holy Ghost fire, fuel joy and embolden people to get through whatever trials come their way. Even when “you can’t really see a solution to what you’re dealing with at the moment,” says Ke’Amber Daniels of Faith and Harmony, singing gospel music will remind you, “Hey, I’m still here; I got what it takes to make it through this. It will give you a sense of peace.”

And even more than a sense of peace, this deep-rooted gospel music creates the sound of what black sacred music scholar Ashon Crawley calls “otherwise possibility.” The sound opens up a pathway that allows us — believer and non-believer alike — to imagine a world better than the one we have; to really see it, hear it, feel it; to know that such a world is possible.

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.