Discover the Piedmont Blues

BluesHow did a culture that influenced the likes of Bob Dylan, the Grateful Dead, and the White Stripes stay hidden for so long? Learn about the Piedmont style and why its culture is alive and well today.

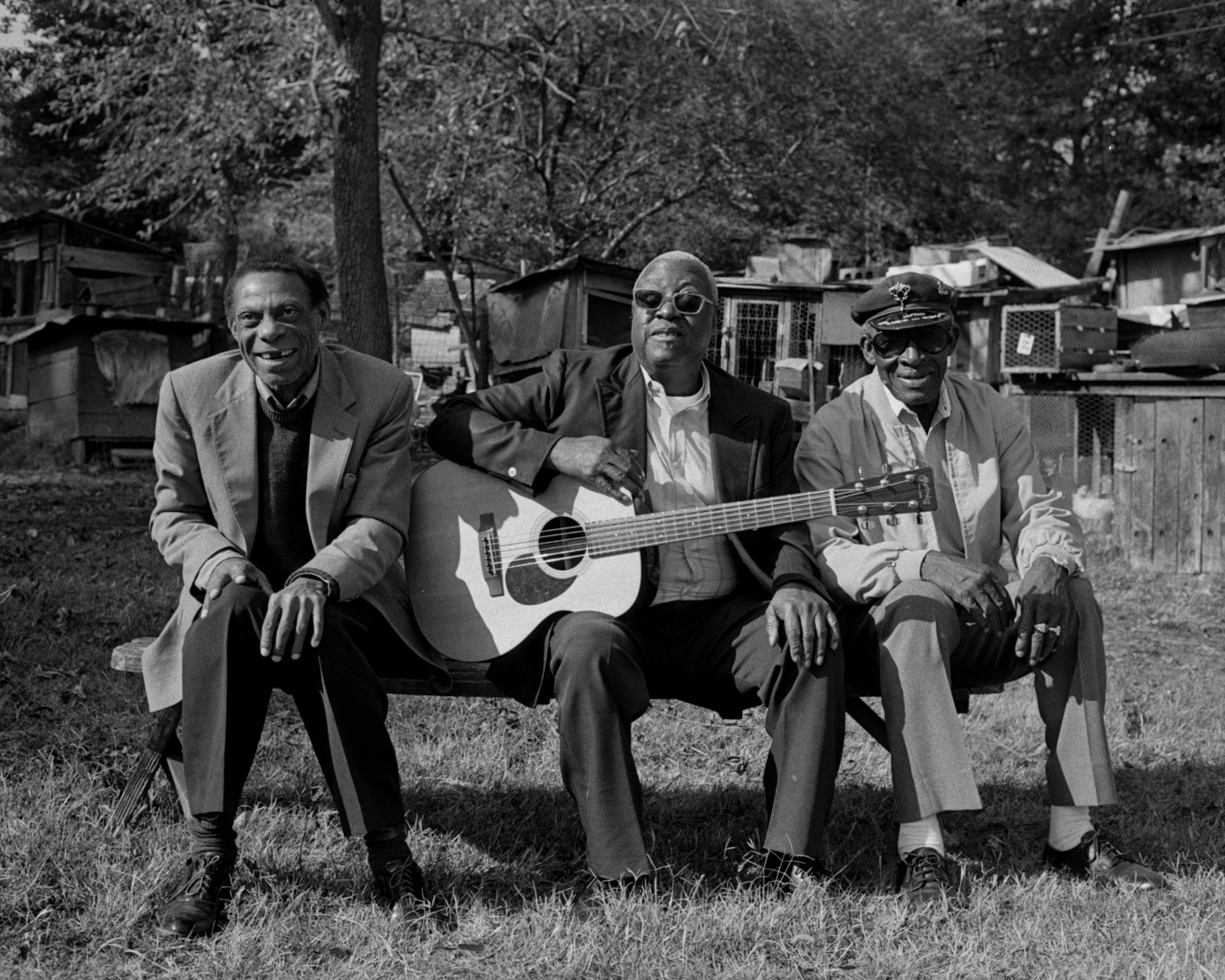

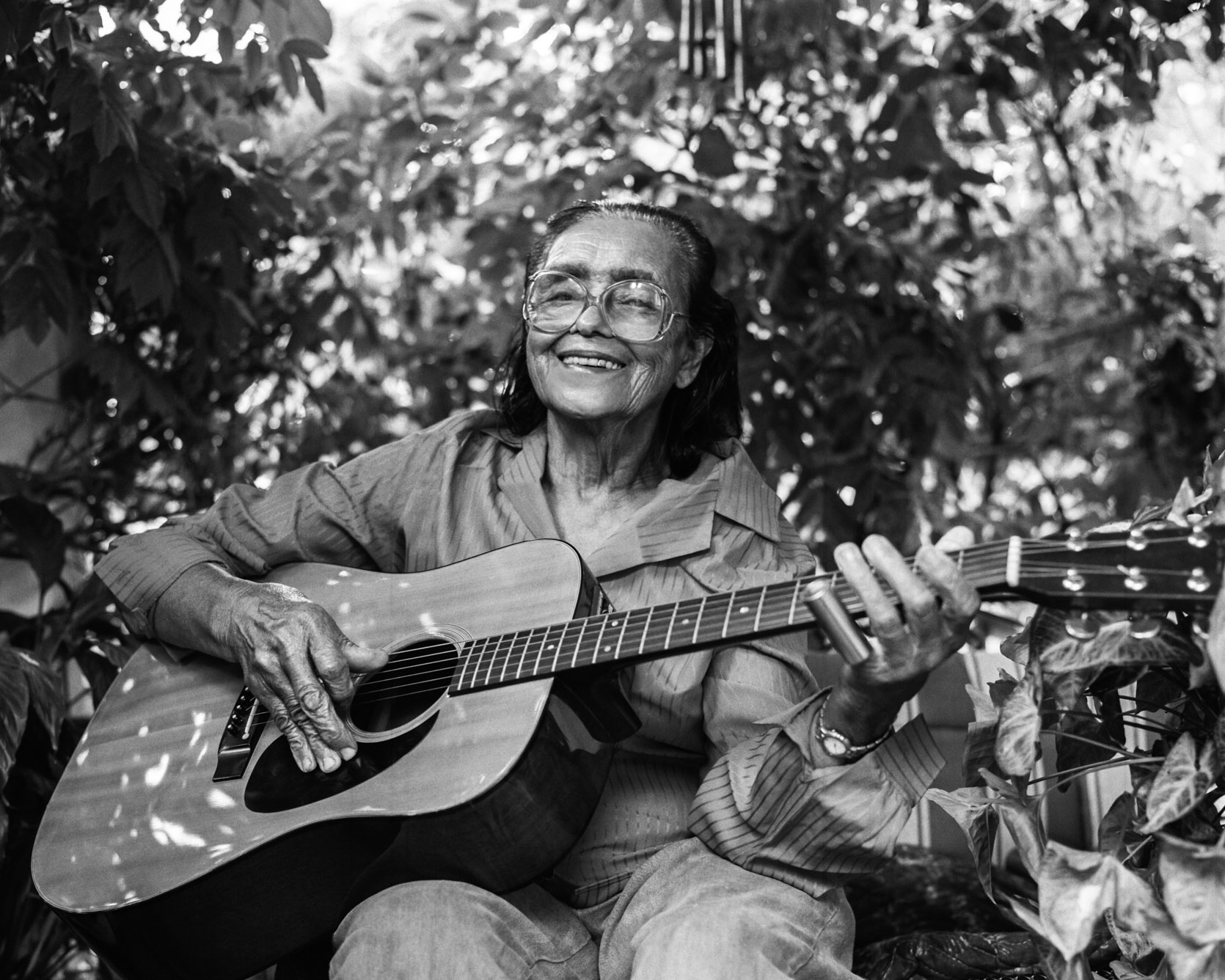

Photo by Tim Duffy.

“Culture Doesn’t Die”

“A small, out of date, half forgotten song tradition” was how early blues field researcher Samuel Charters described the Piedmont or East Coast blues in his 1984 liner notes to a Pink Anderson album. But it’s funny. It’s hard to find something when you aren’t looking for it.

“The standard story of the blues is that it was born in the Mississippi Delta and then came to Chicago and then the U.K., where the British picked it up. But it’s a bigger story than that,” says Music Maker co-founder Tim Duffy. Most modern music fans know the Piedmont blues because modern artists covered its makers’ songs. The Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan covered Elizabeth Cotten. The Dead also covered Rev. Gary Davis, and he was highly revered by the artists of the 1960s folk revival. Dylan, the Allman Brothers Band and the White Stripes performed the works of Blind Willie McTell (Dylan even named one of his own compositions after McTell).

Cotten, Davis and McTell — along with other Piedmont pioneers such as Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, who performed at the inaugural Newport Folk Festival in 1959 — cemented themselves in blues history. But the artists who’ve carried on in the southeastern and mid-Atlantic blues traditions have remained largely unknown to both scholars and record labels.

“It was a story that was not told — and it is delightful music,” Tim says. “Our first years were just finding all these guys in a wonderful, colorful quilt of music.” One reason Music Maker chose Hillsborough, North Carolina, as its headquarters was to be near the homeplaces of the Piedmont blues’ originators.

“Culture doesn’t die,” Tim says. “They thought the Piedmont Blues was dead and not really going on in the ’70s; and then it’s the ’90s and there’s a scene; and now, people like Gail Caesar are playing. That’s amazing!”

And the roots of this music reach all the way back to the 17th century, because most of the enslaved people on this continent were in the Southeast.

A Living Past

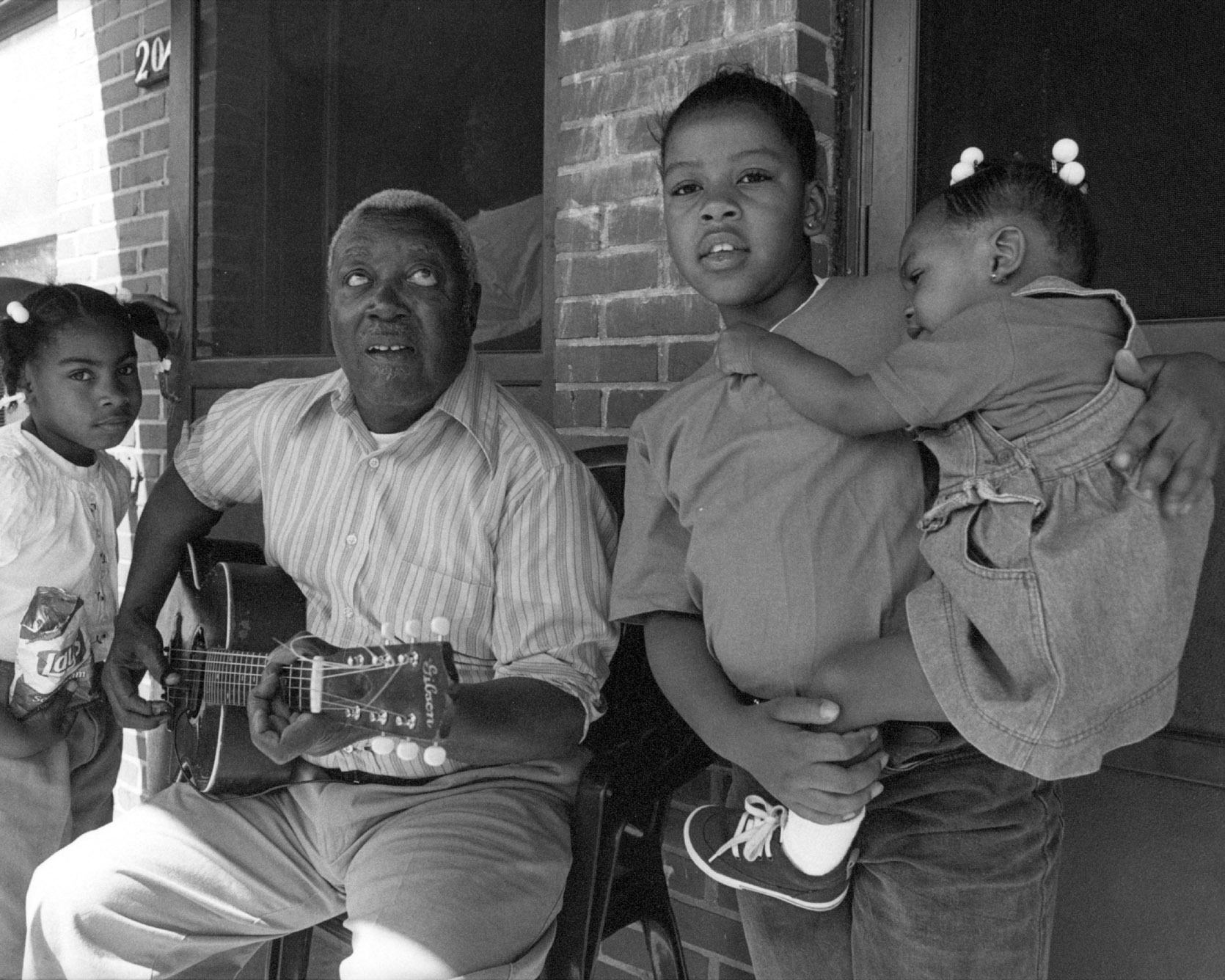

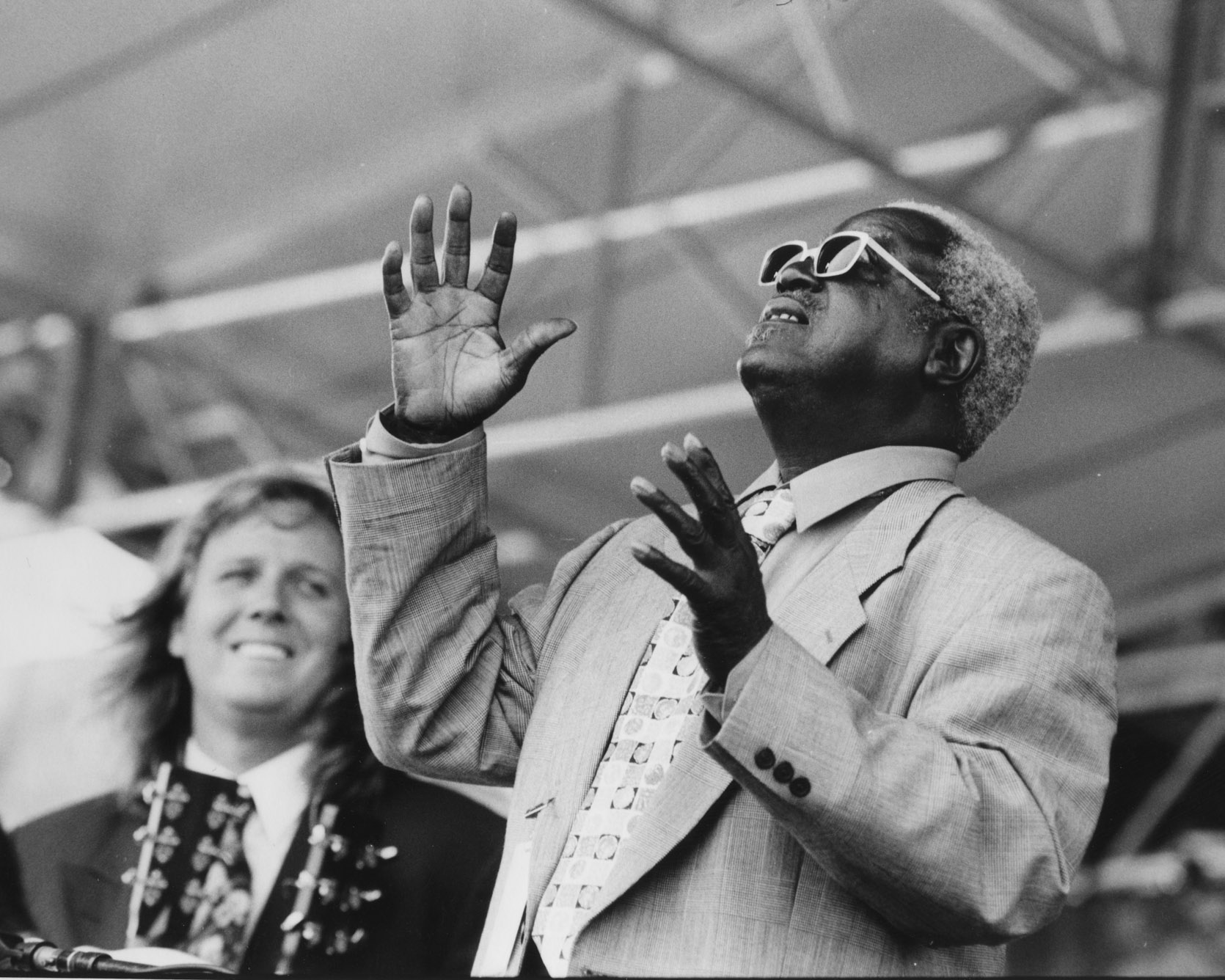

In 1989, Tim interviewed James “Guitar Slim” Stephens, thought to be the last bluesman in his community, for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Southern Folklife Collection. While terminally ill with cancer, Slim suggested Tim track down Guitar Gabriel. He did, finding Gabe in Winston-Salem. That connection opened up a living past — and inspired the creation of the Music Maker Foundation. Tim rebooted the master bluesman’s career, booking dates and touring with him, and soon, he realized the depth and breadth of the Piedmont blues culture that was still alive and well in the late 20th century, not in some foggy past.

Gabriel grew up on a farm in Decatur, Georgia, raised by his sharecropping father, himself a blues player who recorded with Blind Boy Fuller, and his great-grandmother, who was born into slavery and played the banjo. Gabriel had also spent time traveling with medicine shows. Medicine shows were touring caravans of entertainers and hawkers who sold their own “miracle cure” medicinal concoctions. In their early gigs together, Gabe and Tim revived the practice, selling their own “medicinal oil.” Other Music Maker artists who got their start in medicine shows included Stephens and Little Pink Anderson (with his father, Pink).

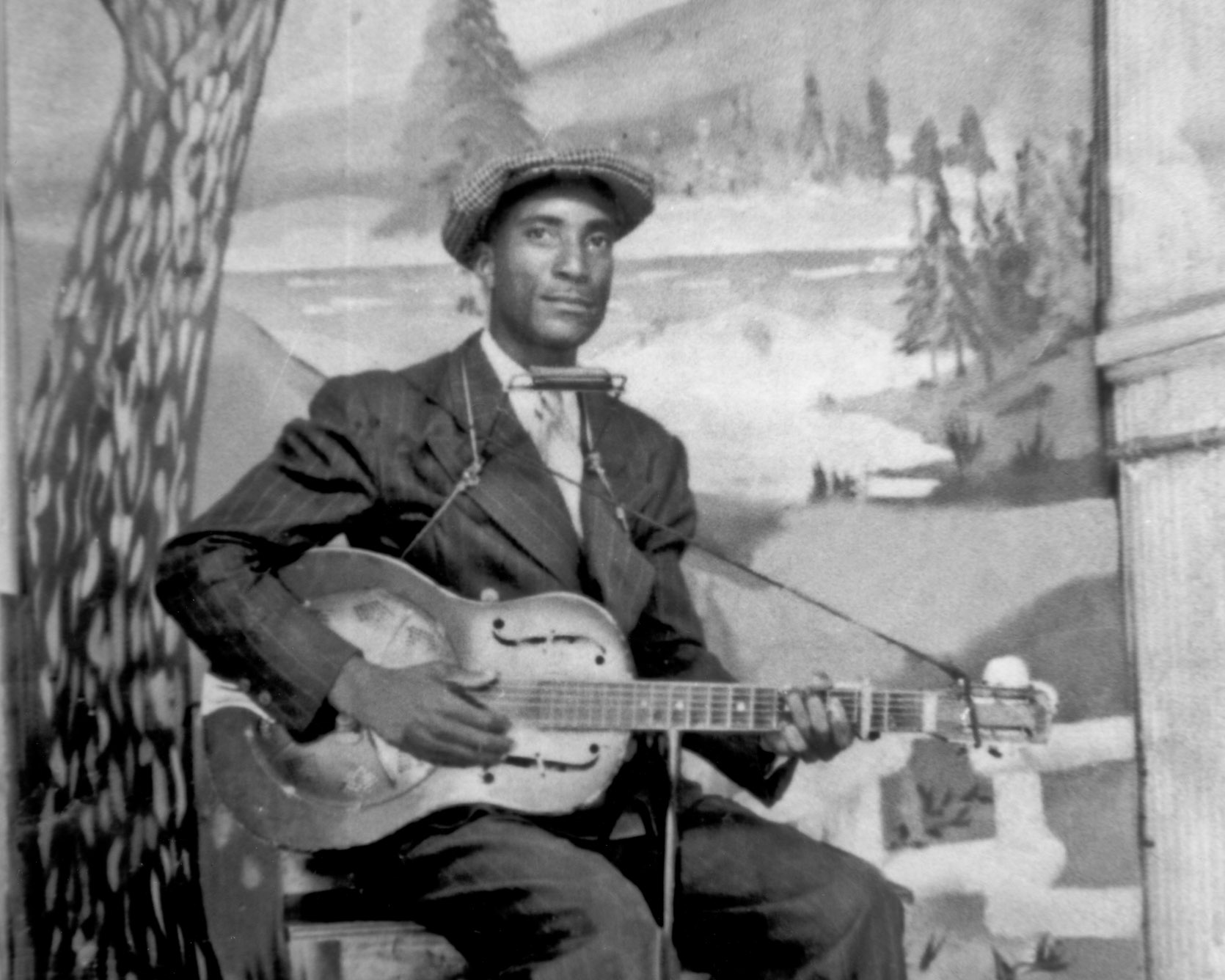

Guitar Gabriel’s musical style demonstrated that the blues from the Atlantic coast was far more varied than is usually acknowledged. Piedmont blues is often defined as more uptempo than Delta or Texas music, with a guitar mimicking a piano, using an alternating bassline and virtuosic fingerpicking, influenced by ragtime piano, gospel, and string band music. There are many artists who played this style, from legends like Rev. Gary Davis, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Blake and Blind Boy Fuller to Music Maker artists such as Etta Baker, Boo Hanks, Little Pink Anderson, Cootie Stark and Cora Mae Bryant. And while each can be placed in the Piedmont tradition, they all had their own unique qualities.

“We didn’t find Piedmont blues — we found highly individual artists,” Tim explains. “There’s Guitar Gabriel blues. There’s Macavine Hayes blues. There’s Etta Baker, Mr. Q, and George Higgs blues.” For example, some played slide guitar, which is generally left out of the Piedmont characterizations, such as Music Maker artists Drink Small, Stephens and Baker.

Mr. Frank Edwards was similarly difficult to pin down stylistically. Friends with Tampa Red, Blind Willie McTell and Cora Mae Bryant’s father, Curley Weaver, Edwards passed away at 93, the morning after his last recording session.

South Carolina’s Drink Small exemplified this varied yet individualistic approach.

“They call me the Blues Doctor ’cause I can play all the styles — bottleneck, ragtime, Piedmont blues, Chicago blues,” Small once said. Born in 1933, he played piano in church and then added guitar to his repertoire, with Fuller’s “Bottle It Up & Go” and other Fuller songs among his first pieces.

As did Small, many Piedmont players integrated styles from other regions into their own playing. Texas legend Lightnin’ Hopkins told North Carolina’s John Dee Holeman that he was the best he’d ever heard at Lightnin’s Texas blues, though Holeman learned to play a thousand miles from Lightnin’.

“When They Hear Me Play, They Think It’s Two Guitars”

By the time Music Maker was founded, Blind Boy Fuller had been dead for 53 years. Yet many Music Maker artists cite him as a touchstone. Some Music Maker artists, such as Big Boy Henry, had direct ties to Fuller. In the mid-20th century, Fuller’s recordings had broken the color barrier in the recording industry: His music sold to white buyers and African Americans.

“He sold half a million records,” Duffy says.

Boo Hanks, a lifelong tobacco farmer from Buffalo Junction, Virginia, just north of the North Carolina line, learned the blues from his father — and his dad’s stack of Fuller records. Hanks’ family lived and farmed tobacco on the same piece of land since the days of slavery. Hanks himself worked on a tractor until he was 85. He played the blues with a “bounce” in his thumb, saying, “Most people, when they hear me play, they think it’s two guitars, because I play the bass and the other strings at the same time.”

“Cootie Stark had a ‘sporting thumb,’ as they would say. It’s hard-driving dance music,” says Tim. The Greenville, South Carolina, street musician learned from figures who would be unknown to even the most serious blues fan, drawing from his uncle Chump, Chilly Wind, and Baby Tate, the latter of whom, Stark said, taught him “thousands” of songs. Stark’s mention of such unsung artists highlights how many musicians never made a record, but still held sway In local communities.

Of Tate, Tim says, “He’s a character that no one really knows about that influenced the guys that I met.” Blind since childhood, Stark performed regionally through the Carolinas, eastern Tennessee, and Georgia, sometimes with Pink Anderson, Peg Leg Sam, and the great Josh White, who later made his mark in the New York folk scene.

Peg Leg Sam left an impression on fellow Music Maker artists George Higgs and Captain Luke, who saw him play when they were young. A one-legged dancer, medicine show performer, joke-teller, and harmonica virtuoso, Sam was “bigger than Muddy Waters around here,” according to Tim.

Tobacco and Highway 40

Tobacco is still central to the lives of many musicians in the region. John Dee Holeman, who was raised on a farm growing tobacco, wheat and corn, once said, “When I came to Durham to sell our tobacco, that’s when I heard talk of Blind Boy Fuller. … I caught it [the blues] from my cousin, who caught it from my uncle, who caught it from Blind Boy Fuller.”

Duffy connects the dots, saying, “I met all those guys in Winston-Salem because the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. was there. A lot of people moved because that’s where the money was.” Tim found musicians all along Highways 40 and 85.

“All these major highway arteries have been there for a long, long time,” he says. “They were great trade paths.” Tobacco fomented the music as the urban centers that sprung up to process it provided performance opportunities. Many blues artists played near Durham, North Carolina’s tobacco warehouses when farmers had just been paid for the harvest, making good money in the process.

Music Maker artist Preston Fulp often performed at the tobacco auctions in Winston-Salem and Durham. Working all week at the sawmill, Preston would make $4.50 and then perform at the auction houses all night Friday and Saturday, often coming home with $100. Fulp, a sawmill worker, was born near Winston in 1915, later hopping a freight to find work in the Midwest and Canada. An injury he suffered riding the rails prompted him to settle down back in North Carolina. Fulp could play country music as well as blues and would play for white and Black dances, house parties, corn shuckings, square dances, and barn dances.

“They Work Me Like a Dog Six Days a Week; I’m Gonna Live Like a King for One Day”

Performances at drink houses, shot houses, dances, and parties marked the Piedmont blues.

“Drink houses are gathering places where people drink corn liquor,” Tim says. “If you were Black, you weren’t allowed to go to bars.” According to spoons player Anthony Pough, the idea was, “They work me like a dog six days a week; I’m gonna live like a king for one day.”

Cora Mae Bryant, the daughter of Georgia guitar legend Curley Weaver, learned her craft in such drink houses. She recalled, “When Daddy came around, I would follow him from house party to house party, meeting up with his friends Blind Willie McTell and Buddy Moss. We would go out three, sometimes four days at a time without sleeping a wink.”

Pianist Albert Smith would throw a house party every week.

This celebratory atmosphere grew from the music’s purpose: It was played for people to dance to. Several Music Maker artists were dancers themselves, including Holeman, Little Pink Anderson, and Algia Mae Hinton, dancing steps like the slow drag, buck dancing, flat-footing, and kickin’ mule. Pink, born in 1954, once said, “I would go out and I would tap dance to the music they were doing.” Other dances were never documented and are now lost. Hinton raised seven children in Johnston County, North Carolina, all while performing and laboring in the cucumber fields.

Precious Bryant, of the small town of Waverly Hall, Georgia, also grew up farming and learned to buck dance from her father. She first learned how to play a banjo before switching to guitar, playing along to songs on the radio and playing at parties. “When I’d get home I’d have a guitar full of money,” she recalled.

“You Can Change It Around, Give It More of the Blues”

Etta Baker, one of the Piedmont blues’ all-time greats, learned to play music from her parents and grandparents, who moved from North Carolina to Virginia one year before she was born in 1913. Remembering the moment that the then-new style of blues transformed the household’s music, she said, “Daddy played what we called folk music. Daddy played ‘Careless Love.’ You can change it around and give it more of the blues.”

Baker was a wonderful guitar and banjo player and a beautiful woman descended from Black, Irish and Native American ancestors. She was discovered by the folk musician Paul Clayton in 1956 and a few years later was offered a chance to play the Newport Folk Festival, but her husband demanded she stay home. It wasn’t until the 1990s, when Baker formed a partnership with Music Maker, that she began recording her own albums.

Piedmont blues women generally performed more often at home than their male peers. Etta said, “Just about everyone, you know, all the women back in them days, just about everybody came by, played some kind of string band music. … The whole mountains was ringing with Carolina blues.” Tim says there were sometimes stylistic differences between genders, too.

Tim wonders if history has blind spots, asking, “How many other women artists were there? We just don’t know who they are. You couldn’t get past their husbands and their family, and no one was looking.” Social conventions left women much more tied to their homes. It was not considered proper for wives and mothers to travel and perform in drink houses, juke joints and bars.

To Baker, the Piedmont blues was a joyful sound. She said, “I like the Piedmont blues because they’re more gay, more happy. … It gets on your mind heavier than your ailments do, I think. … I find a lot of happiness in it.” Cootie Stark put It this way: “People come in fussing and fighting and leave hugging up.”

The artists who played in the Piedmont style would be proud to know their tradition continues today with musicians like Jeffrey Scott and Gail Caesar, both of Virginia.

The late Piedmont player George Higgs once said, “It’s not so much the money, I just want the sound to keep on. My whole idea, my hope, is that we can keep it alive, this old tradition.” Little Pink Anderson today echoes Higgs, saying, “Just being perfectly honest, I’d like to see America appreciate the music more because it is American music.”

– Nick Loss-Eaton

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.