Discover Music Maker Studios

FeaturedBy Stephen Deusner

Along Wilson Street in Fountain, North Carolina, a sleepy farming town in the eastern end of the coastal plain, sits a storefront whose windows are full of old posters, concert bills, and Hatch prints. It’s a colorful history of blues and rock and R&B, representing everyone from Jackie Wilson to Howlin Wolf to Joe Simon, and behind those posters, nestled in this recently refurbished hundred-year-old building, is a homey, state-of-the-art recording studio designed to build on that history. Built by Music Maker Foundation, it’s an extension of the organization’s mission to preserve distinctive regional music and to support the artists who still make it. The studio, which has already hosted several sessions before its official grand opening in October, is already attracting blues and folk artists from around the South to collaborate with artists from this region.

“We’re meeting the musical culture where it exists and we’re trying to be a part of it,” says Timothy Duffy, who co-founded Music Maker Foundation in 1994. “This studio gives Music Maker a physical place to grow and fundraise and create, and we hope other organizations will join us here in Fountain. It’s going to be a centerpiece for all of our programming, because it’s such a great way of nourishing the music community.”

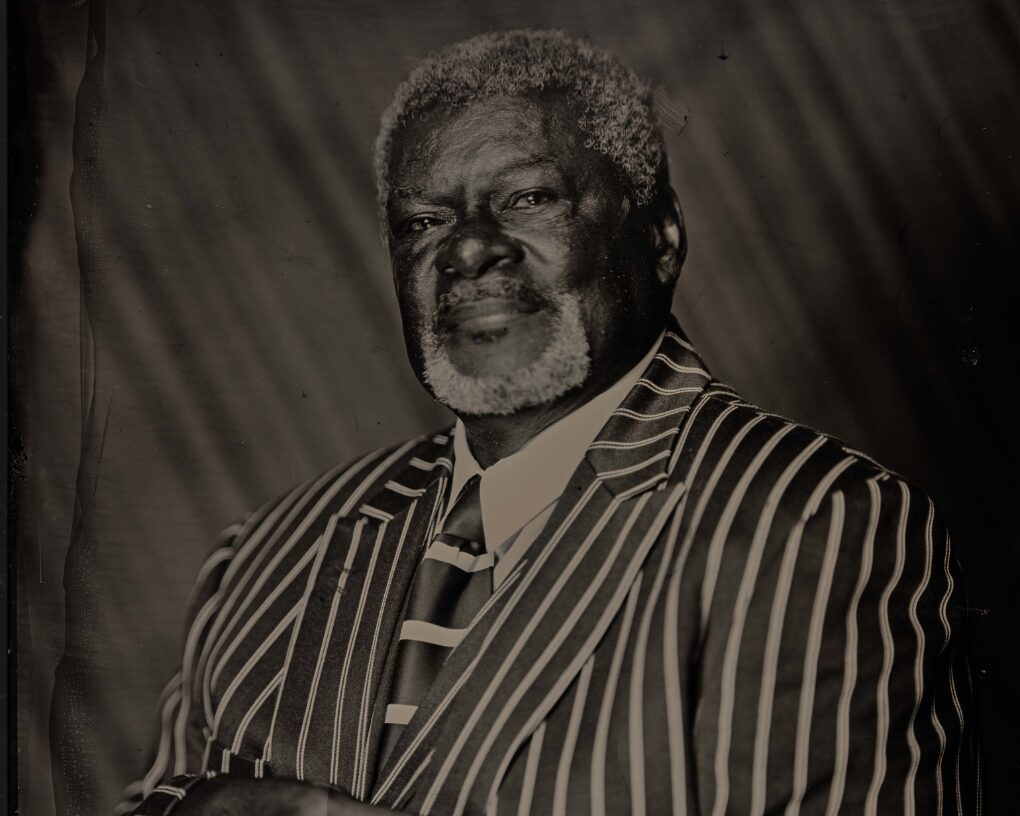

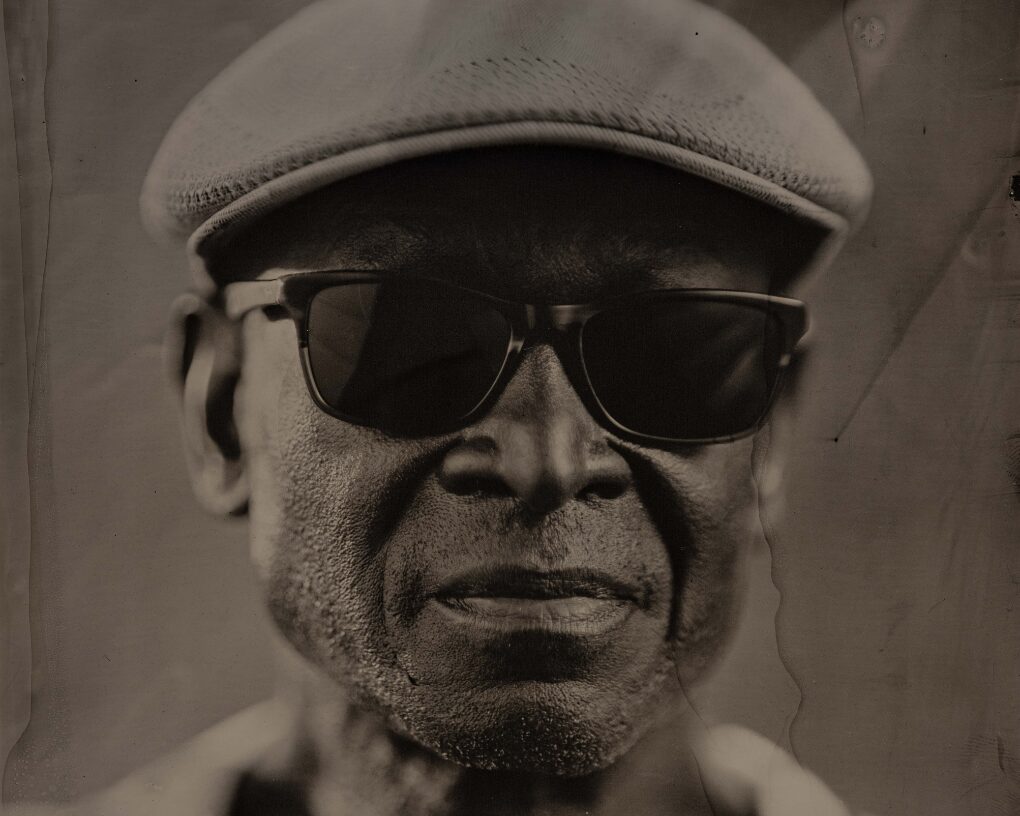

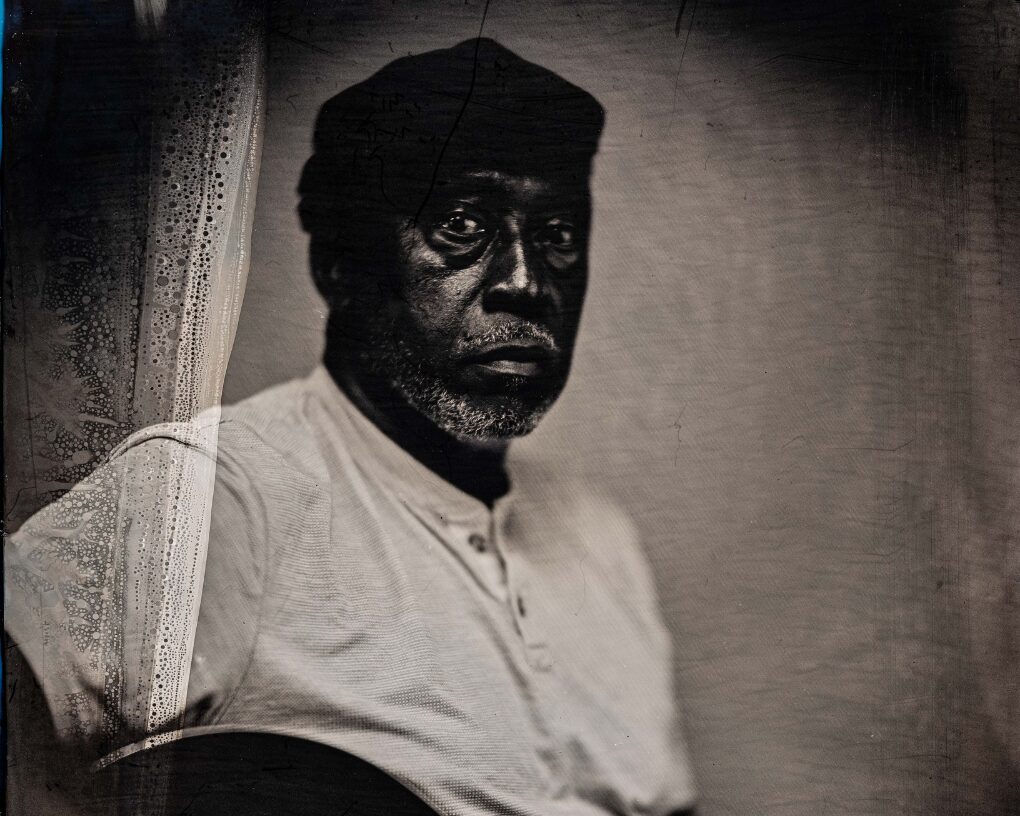

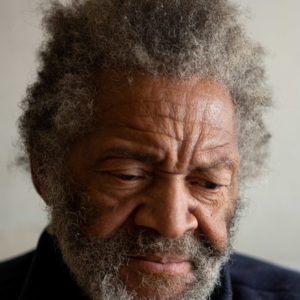

Music Maker envisioned the studio as an immersive experience: a place where artists would have access to everything they need with as few distractions as possible. In fact, nearly every step of the record-making process can be accomplished here on Wilson Street. There is space to rehearse songs and work out ideas, an acoustically distinctive live room for tracking, and state-of-the-art equipment to mix and master the final album. Once that’s done, artists can walk next door to the photo studio and sit for professional shots or tintypes (the specialty of Duffy himself). “When you come to this studio in Fountain, you come to a place where there are really no distractions,” he says. “The studio has a live room, gear storage, laundry, a large kitchen that will seat ten people—everything you could need. It’s all deep in the country, where you can feel a little time out of mind. It’s the perfect place to create.”

But the recording studio also offers inspiration in the form of handmade guitars lining the walls. Many of them were made just two doors down in the workshop of Freeman Vines, a contemporary artist who has for decades been working at the crossroads of visual art and musical tradition. He crafts intricate instruments using reclaimed lumber, including wood sourced from lynching trees around the region, transforming the South’s ugly, violent history into the tools necessary to create a better future. His work is visually striking: gnarls and knots of wood forming faces or abstract shapes, some painted bright colors and others left the natural shade of the wood itself.

The recording studio has the look of an art gallery, but Vines’ guitars serve a dual purpose: Artists can actually take them down and play them, an act of preserving their tone and sound on tape. “It’s constantly inspiring to see those instruments on the walls, but they’re not just art pieces,” says Jimbo Mathus, the legendary roots artist who serves as the studio’s house producer and bandleader. “There are all these incredible hidden things you can’t even see and wouldn’t know about unless you played them. Freeman is a master luthier, and he likes to experiment with different tones. His guitars are living, spiritual things, and they’re definitely affecting the music we make there.”

This row of workshops and art spaces actually sprang from Freeman’s imagination. In 2019 Music Maker purchased the storefront that houses his workshop, and he can be found there most every day, carving his next creation. The building once served as the town’s pharmacy, and the shelves that once held medications and tinctures are now heavy with guitars in various states of completion, well-used woodworking tools, spare necks and frets, tangles of electrical innards—all the raw materials of his visionary art. “Everything I need is here all together,” Vines says. “So I can just sit and listen to the wood. If you work with something long enough, it starts to communicate with you. The wood has a way of helping you along, telling you, No, don’t cut there. Cut here. And I’m listening.”

Once he was settled in, he suggested to Duffy that the Music Maker Foundation buy more storefronts where other artists could set up and create. “I had the idea that they should do something here in Fountain, and I mentioned it to Tim,” says Vines. “I forgot all about it, but never lost interest. He made it happen.” Soon they had refurbished a second building and opened the photo studio. To design the new recording studio, Duffy and his wife Denise Duffy collaborated with a crew that includes Bruce Watson (who runs the labels Big Legal Mess and Bible & Tire) and Mathus (who serves as the new studio’s house producer and bandleader).

The studio gives the foundation a stronger physical presence in rural North Carolina; its main offices may be up the road in Hillsborough, but its soul now resides in Fountain. That is already making a difference in a town that lacks the populace to support many businesses. Like many rural communities across the country, Fountain has dwindled and shrunk over the years, but Music Maker is redefining the town in a fundamental way. “What we’re looking for is an identity,” says Mayor Kathy Parker. “Fountain was incorporated in 1903 and used to be known for agriculture, but that’s gone now. It’s a very sleepy town, but I’m excited about Music Maker’s presence because I would love for Fountain to be known for original Southern music.”

Already Music Maker Studios has hosted several sessions by artists from around the South, including the Piedmont-style finger picker Shelton Powe, the Georgia guitar veteran Albert White, the Houston-based artist Leonard “Lowdown” Brown, and “bluejazz” pioneer Earnest “Guitar” Roy. With Mathus and his touring group as a versatile house band—a model based on similar outfits at Stax in Memphis and Fame in Muscle Shoals—a distinctive sound is beginning to emerge in these recordings, one that is traceable back to this place rather than to a computer program. “The studio has a great, distinctive live sound,” says Duffy. “We’re recording completely old school, with everyone in the same room with complete bleed everywhere.”

The studio serves a large, yet under-resourced community of gospel artists working in this region—in particular the large and legendary Vines family, which includes Freeman himself. Three of its members have formed a small choir called The Crimestoppers to sing backup on nearly every record made in Fountain: Anthony Daniels from the group Dedicated Men of Zion and KeAmber Daniels and Christy Moody from Faith & Harmony. “When we were recording Roy,” Mathus recalls, “Freeman sat in the big room while his family was singing, and he was just beaming with pride. His guitars were hanging on the walls, and his family is in there singing so beautifully together. His whole face lit up. And that’s what it’s all about. At the end of the day, it’s about giving these artists their due and helping them make something that will last.”

The Fountain complex is a profound step forward for the Music Maker Foundation as well as for the music community itself. “Documentation has always been a big part of what we do,” Duffy explains. “We’ve traveled to various studios in order to pursue that goal, but now we have this central focus—a place where people can come and retreat and reflect on their music and create something special.”

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.