Discover “Hanging Tree Guitars”

BluesSculptor and art guitar maker Freeman Vines’ revelatory “Hanging Tree Guitars” project — now an acclaimed book and exhibition featured on NPR and in Rolling Stone — reveals an unspoken American history and gives voice to those silenced.

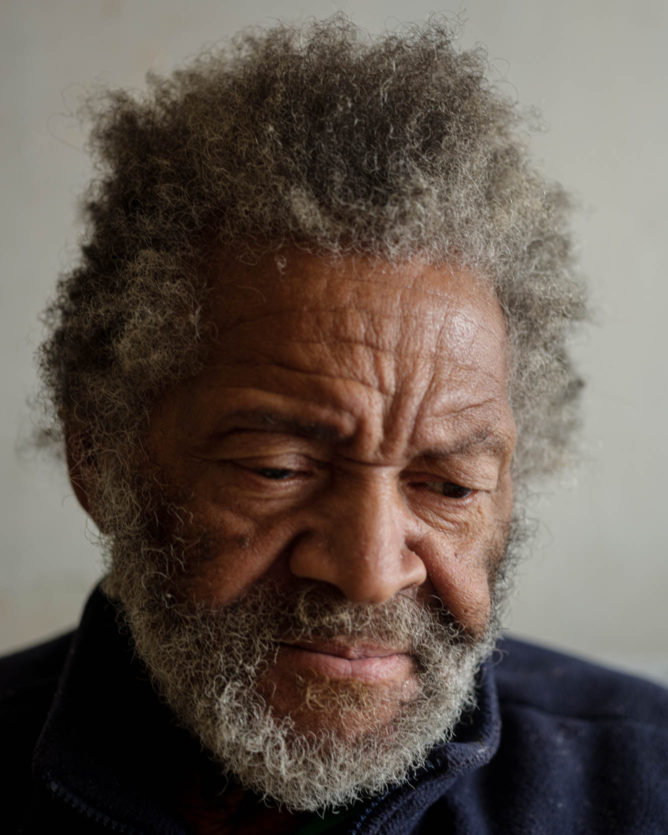

Freeman Vines has been building guitars for 50 years, and no two are alike. While commercial guitar companies like Gibson or Fender seek uniformity in their instruments, Vines seeks singularity. He doesn’t force his raw material into a predetermined form. Instead, he follows its lead. He closely considers the unique qualities of the wood and allows his own artistic spirit to connect with the wood’s character and its history.

This material might be an old mule trough, a torn down tobacco barn, or a broken piano. Or it might be a hanging tree. Three planks of wood from a tree that was used for a lynching would lead Freeman — and Music Maker’s Timothy Duffy — on a spiritual journey through unspoken truths and buried histories about America. And that wood led Freeman to create remarkable works that would bring them to museum stages worldwide and to spotlights in NPR, Rolling Stone, and Smithsonian Magazine.

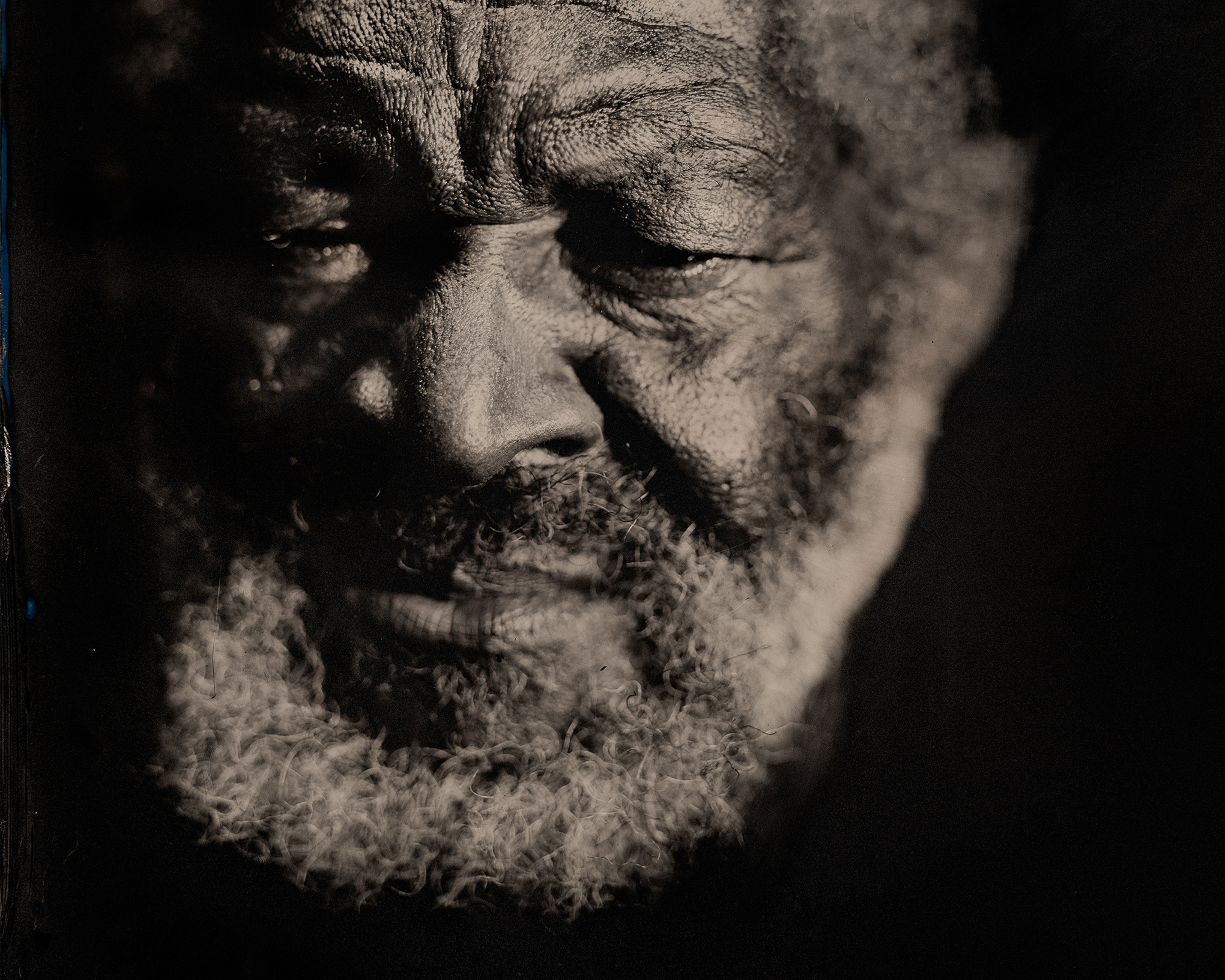

Top photo by Tim Duffy.

Following the Sound

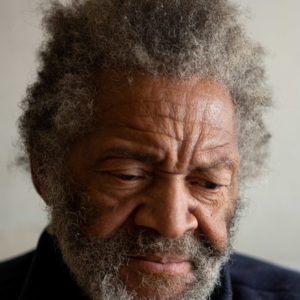

Vines was born in the 1940s in Greene County, in the eastern part of North Carolina, not far from where he lives now in the small town of Fountain. He is the oldest surviving son in a family of 11. His mother was a sharecropper, and after three years of school, he quit to help her in the fields. These were some of the same fields worked by his enslaved ancestors who were brought to this area in the early days of British colonization, more than 300 years ago.

Growing up in the Jim Crow era in the rural South, Vines was surrounded by racism. As a teenager, he got in trouble with the law for selling moonshine. His white partners-in-crime were released, but Vines went to jail. He spent years in both juvenile and adult prison facilities. He learned to read and write in the penitentiary. Sometimes, he jokes, couching harsh truth in humor, “The college I went to is spelled ‘C-H-A-I-N G-A-N-G.’”

Vines learned to play guitar, soon discovering that the Carter Family’s “Wildwood Flower” wasn’t that far off from the blues he was also learning. He would hear music in “shot houses” (juke joints) as often as he could.

During this time, Vines became obsessed with a sound he had heard. Maybe a guitar riff in a church, or a mysterious howling at night. It was a sound with its own kind of force, drawing him to it. He wanted to bring it out of a guitar. But the mass-produced guitars he had played weren’t up to the task.

“All the sounds to me were commercial,” he says, “plain, dang, ding, dong.” So he set out to build an instrument that would produce the sound he heard in his mind.

That was the beginning of a long journey. Using materials from his surroundings, he built one guitar after another. Each was different: different shapes, different hollowed-out tonal chambers, different configurations of electronics. Vines amassed a totally unique body of work as he searched for his sound.

“The closest I found,” Vines recounts, “was a piano soundboard, and I said, this is the closest I’ll ever come. That’s when I kind of gave up looking for the tone.”

Deepening His Craft

He didn’t stop building guitars, though. In abandoning the quest for the perfect tone, Vines granted himself more artistic freedom in the design of his guitar bodies, sometimes creating works that were more sculptures than musical instruments. The inspiration from the material itself became even more palpable. In many of his creations, Vines says he simply worked the wood to reveal what was already there.

By 2015, Vines’ work had slowed considerably as a result of his poor health. This was when Tim Duffy — co-founder of the Music Maker Foundation — met him. As a folklorist and photographer, Duffy had decades of experience working with brilliant artists who had deep roots in the oldest African American traditions, and he instantly recognized Freeman Vines as someone special.

On the day they met, Vines brought out his guitars, and Duffy was shaken to his core. The designs were unlike anything he had ever seen, but more than that, there was an unmistakable harmony between the instruments, the land, and Vines himself.

The guitars were alive with their past purposes. The vibrations from the weight of the foot that trod on the front step of the tobacco barn. The slobber of the mule that drank from the wooden trough.

It was on this first visit, with Duffy reeling from his encounter with this powerful work, that Vines showed him the hanging tree wood. He had acquired three planks of black walnut wood from an old man who told him it was from a hanging tree. Vines had not tried to build anything with it yet, but Vines was already thinking through what he would do with the wood. He showed Duffy two drawings, one of a skull hanging from a tree branch, the other of a guitar hanging by a noose from a tree.

Soon after, Music Maker helped Vines get access to the health care he needed. Before long, he was regularly working on new guitars. As Duffy continued to visit, he realized more and more that Vines was not just an artist, but a philosophical man with a deep feeling for history, a powerful connection to the land, and a complex sense of spirituality. Vines expressed this all in his own highly poetic language. He talked often about the hanging tree wood.

Vines completed his first guitar from this wood in 2017, about two years after meeting Tim Duffy.

“When he mentioned the hanging tree guitars, I was too scared,” Duffy said. “I was almost too scared to take the project on. I didn’t think I had a right to do it. I thought I was crossing into territories where a white person wasn’t allowed to go.”

But Vines was gripped by the hanging tree guitars project. As he worked with the wood, he wasn’t just making unique guitars, but reaching back to the past, giving voice to history, and recovering stories that were crying out to be told. Duffy and others, including folklorist Zoe van Buren, joined Vines on a quest to better understand the origins of these stories, listening to Vines tell them about the lynching of Joe Black and other lynching memories that Vines had. Their research then led them to written accounts of Oliver Moore, a 29-year-old black man who had been lynched in 1930 just a few miles from where Freeman Vines was currently living in Fountain. People in the region still won’t talk about the lynchings, though they finally got corroboration on the origin of the wood.

Lynched in 1930, Oliver Moore Reaches Out Through Time & Wood

Oliver Moore’s lynching was widely covered in the press when it happened. However, no one was ever convicted of a crime. White people were scared that they would be seen as traitors if they turned someone in. Black people were scared that they would be next. Silence hung in the air like a dark cloud and persisted for decades, into the present.

If humans struggle to communicate openly and reckon with the past, the land nevertheless holds the memories. For Freeman Vines, the spirit that animates human souls also lives in the land and the trees. The hanging tree held the story. And not just the facts of the story, but its emotional and spiritual complexities as well. His work was revealing all of this, and boldly breaking the code of silence that had reigned in the community for so many decades.

A series of guitars with haunting skull and snake imagery followed the revelation of Oliver Moore’s name. In particular, Vines was struck by the discovery that Oliver Moore had been shot 200 times, an excessiveness that takes the lynching beyond mob violence and into the realm of ritualistic performance.

The last piece Vines made wasn’t a guitar at all, but a shoe. Moore had worked as a cobbler. But Vines didn’t know that.

“When you take the wood, and set there and look at it long enough, it’s already there,” Vines says. “All I did was cut it out, sand it down to get the edges off, and there set a shoe.”

As Vines completed his works from the hanging tree wood, he, Duffy, and Zoe van Buren worked together to create a book entitled “Hanging Tree Guitars.” Van Buren extracted passages from hours and hours of recorded conversations and presented these in such a way to allow the story of the hanging tree guitars to emerge through Vines’ own uniquely poetic voice. Accompanying this text are some of Duffy’s tintype photographs (a striking form of photography that dates back to the 1800s) of Vines, his guitars, and his rural surroundings.

“I spent weeks and weeks trying to take pictures of these things,” Duffy says “I had to spend a lot of time just looking at them, for about six months. … I shot a hundred 12-by-20-inch plates in 28 days. The physical effort to do that in the month of August: bottles of collodion bursting. Sweating. It was grueling work.”

The process terrified Duffy at times. “I attempted to capture the horror Freeman felt from the blood that was in that wood. Of course, it is in the wood,” he says.

This book set the stage for the current traveling and online exhibition, its companions.

Ultimately, Hanging Tree Guitars zooms in on only a small part of Freeman Vines’ body of work. For around 50 years, he has been a prolific guitar builder and artist. This particular collection, however, provides a stark example of just what a masterful artist he is.

Exhibition and book debut at the age of 77

Since its release, Freeman has had works in a group exhibition at London’s Turner Contemporary and in a group exhibit at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, alongside works by Kara Walker and the guitars of Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry. He has seen his book profiled on air by NPR, then named one of the outlet’s best of 2020 in six different categories. Tastemaking artists like Carrie Mae Weems and folklorists like William Ferris dug into Vines’ work. It inspired Music Maker to create an accompanying compilation of blues and sacred soul music on the subject of race in America, which was named the best album of 2020 by Robert Christgau. Vines was the subject of a mini-documentary by NowThis News!, which was viewed over half a million times. He also did a series of conversations with cultural figures, art curators, artists, musicians, occult experts, folklorists, and more.

Music Maker has given Vines a studio in which to work and also assisting with medical care as he had to have one eye removed due to glaucoma.

As Zoe van Buren writes in the afterword of “Hanging Tree Guitars,” these instruments “offer an unsettled — and unsettling — look into how history is written into the land and the mind. The stories that Vines tells of labor, violence, cross-racial entanglements, and spiritual resistance are stories that define the history of the South itself.”

Finally, while this exhibit and book are full of heavy and even dark content, Vines hopes visitors will not lose sight of the joy that is also here. For all of Vines’ intensity, he’s also a funny man, full of dry wit. When he puts his gifts to work, there is an element of fun, even playfulness, in how he transforms his material into a finished product. It is, after all, guitars that he makes, instruments intended to create harmony and bring music into the world. He says, “Have you ever been in a form of meditation? Where you just think, and you’re comfortable. That’s how you feel when you work on it.”

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.