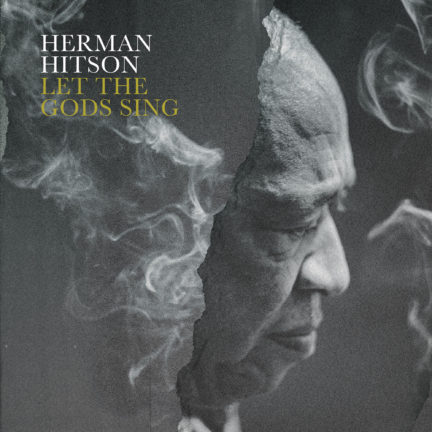

Hermon Hitson

BluesHermon Hitson’s guitar playing is funk, soul and psychedelic rock magically rolled into one. He comes by it honestly, having played with the likes of Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Joe Tex, Bobby Womack and Wilson Pickett.

Arguably, the original seeds of psychedelic rock were planted after Hermon Hitson and Jimi Hendrix became running buddies in the early 1960s. Both were playing the Chitlin’ Circuit, tours that would load somewhere between 10 and two dozen African American musicians on a bus and tour the South, playing Black nightclubs. The two spent weeks together, Hermon says.

“Me and Jimi used to stay up all night, sitting on the bed, eating soda crackers and sardines, and drinking Coca-Cola and Pepsi,” Hermon recalls.

He moved from there to straight-up soul music, recording his own compositions — including the luscious “Been So Long” — in Atlanta for labels like Royal, Atco and Minit. As the 1970s rolled in, Hermon wound up playing funk guitar, recording some tracks with the Ohio Players and releasing some of his own funk singles, including the powerful “Ain’t No Other Way,” a number firmly in the James Brown vein.

Hermon’s ability to move effortlessly across genres also comes from the way he soaked up and learned music throughout this childhood — a process that that led his to believe that all music is “one music.”

Perhaps it’s best to let him tell that story.

“I was born in Philadelphia in ’43,” he says. “Then my father died, and my mother took me down where her people was, and that was in deep Georgia — a place called Ocilla, Georgia.” The tiny town, with population under 4,000, sits about 80 miles north of the Florida line in south central Georgia.

“I was only listening to country,” Hermon recalls. “And those guys really, really excited me. There was no Black radio for me to hear the Black guys doing music. So, country was all I knew besides gospel.”

To build a better life for her children, Hermon’s mother moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where her brothers were, then soon moved Hermon and his brother there.

“That’s when everything busted out,” Hermon says. “I began to see these guys walking down the streets, man, with the head rags on their heads, with guitars tied around their neck, the harmonica blowing. I would see them sitting in front of me at the barbecue joints. They’re sitting and they’re drinking. These guys influenced me. It was the blues, man. I had the gospel and the country. Now, here I am, and all this mixture became one music to me.”

Once he hit New York City, he reunited with Jimi Hendrix, and the music they produced together — before Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham took Hendrix to Long to form the Jimi Hendrix Experience — laid the groundwork for the psychedelic rock of the 1060s and early ’70s.

Today, all the styles Hermon has picked up along the way comes out of him as one music — an incredible mesh of sound. It stuns even those who play with him. Hermon joined the Music Maker Blues Revue at the Telluride Brews & Blues Festival in 2021, and Sam Duffy, brother of our co-founder Tim Duffy and a player of the electric mandolin played with him there.

“I’m walking off stage and I’m like, ‘Hermon, how did you … what were you doing on your guitar?’” Sam said. “I usually don’t bug the guys. But I just accosted him as we were walking off stage. ‘How did you do that? What is going on here?’ He just smiled at me. He said, ‘I don’t know. I just played the guitar.’”

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.