What's in a Name?

By Max Brzezinski

A name works as a hinge between private and public identities. Think of your own name: it’s an intimate part of your subjective experience, and feels hard-wired into your sense of self.

But your name was also given to you by someone else before you could speak, and plucked out of history and from a pre-existing system of naming conventions. Your name is irreducibly you, yet you share it with others, and it predates your birth. A name is abstract and particular: it helps categorize and individualize you at once.

So when we change our name, or take on an alias, we’re doing a lot more than just altering a word or two. We are wagering that we can change the meaning of our lives through a change in language: not only for the world, but for ourselves.

People change their names for all sorts of reasons, and, in turn, it changes them. Saul needed to become Paul in order to break with his past as a persecutor of Christians and seal his born again status; trans folks change their names when they’ve outgrown their old ones; Latter-Day Saints are given secret temple names that purportedly come with divine wisdom. Criminals invent or steal identities to hide and/or start anew, and immigrants often take on new names in transit. It might be better to ask: what’s not in a name? Naming is the dense site where self-fashioning, family history, spiritual and religious practice, and late-capitalist branding collide.

And musicians, of course, have a long tradition of colorful pseudonyms, spanning from before Billie Holiday to today. The wide-ranging array of names in the Music Maker universe are no exception: there’s a whole taxonomic ecosystem at play.

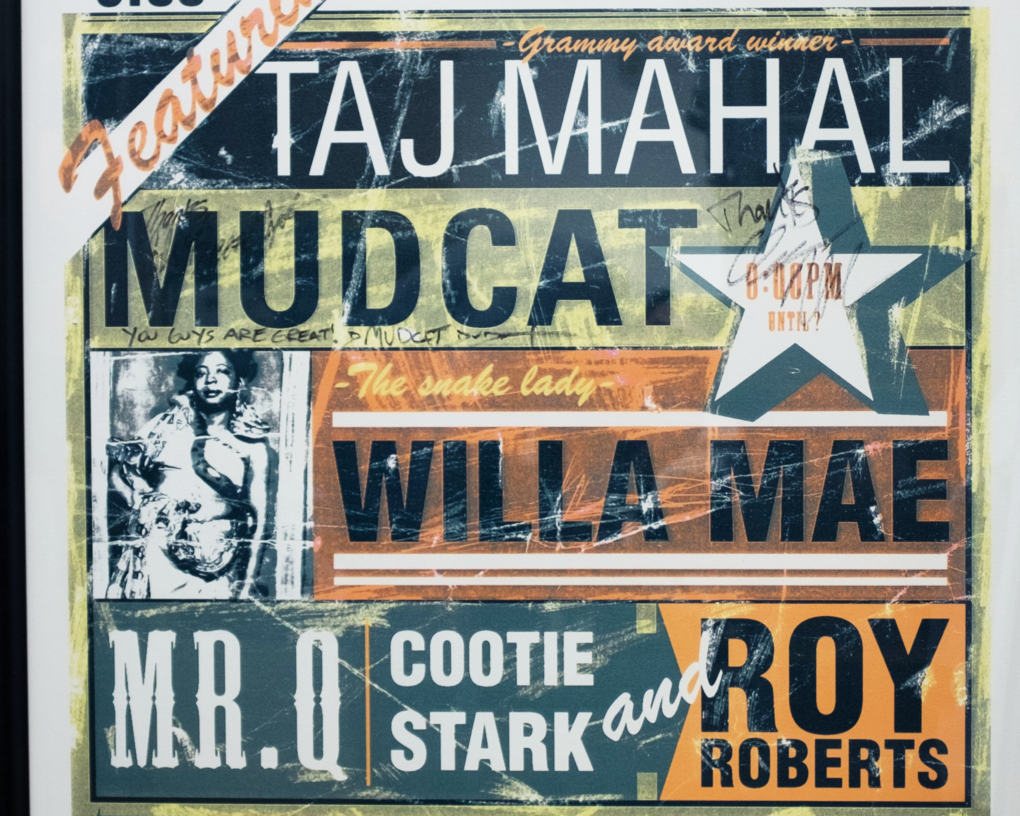

First, there are the games of size and scale played by Lil’ Jimmy Reed, Little Freddie King, Little Pink Anderson, and Big Ron Hunter. The Lil’s and Littles insert them into a blues lineage, and disambiguate them from other famous figures in musical history. But the Big in Big Ron Hunter also has a more literal function: Big Ron’s a burly guy, and his sound’s booming! Or consider the shortening of pianist Cuselle Settle’s hard-to-spell name into the catchy sobriquet Mr. Q.! As MMF’s Gabi Mendick suggested, we can trace the thruline from blues names to rap names: think of Big Daddy Kane and the Notorious B.I.G., Lil’ Wayne and Lil’ Kim, Master P, and so on: they all harken back to a long tradition in musical renomination.

Other Music Maker stage names invoke vocation: Bishop Dready Manning, Brother Theotis Taylor (cf. Sister Rosetta Tharpe), Elder Anderson Johnson, Dr. Burt (cf. Dr. John), and Captain Luke (cf. Captain Sensible). Religious honorifics, like flat job descriptions, project authority and prestige. But the more colorful cognomens, more figurative, perhaps are job descriptions for jobs that don’t yet exist but should: the world might be better with more blues doctors and vibe captains amongst us. And as for the artists with an instrument in their nicknames, like Beverly “Guitar” Watkins, Guitar Gabriel, Guitar Lightnin’ Lee, Charles “Sugar Harp” Burroughs, Terry “Harmonica” Bean, Ironing Board Sam? Well they have an instrument in their name, and it announces they can play the damn thing!

Many MMF personas spawn from family nicknames, derived from resemblances, childhood personality traits, or inside-jokes: Bubba Norwood, Cootie Stark, “Sugar Chile” Robinson, Rip Lee Pryor. A childhood nickname taken into adulthood implies an enduring connection to one’s forebearers and the people one grew up amongst.

And after a while, it’s hard to imagine these musicians with any other name (although Cootie Stark did also go by “Sugar Man,” and Mr. Frank Edwards also went by Mr. Cleanhead and Black Frank). Pat “Mother Blues” Cohen draws on the family metaphor in order to transform the entire blues genre into a community. Lakota John’s name similarly invokes an entire community, in this case, tribal. And Taj Mahal’s stage name, which came to him in a dream of Gandhi, even manages to evoke a vision of global peace!

Still other Music Maker names associate them with a particular region, like Alabama Slim (and Mississippi John Hurt before him). Some monikers fail to catch on, fade with time, or aren’t actually assumed names at all. Drink Small will swear he was born Drink Small (something Whistlin’ Britches could never claim), Precious Bryant just happened to have a precious guitar tone, and Freeman Vines’ handle manages to capture his many-sided being in two brief words, seemingly too fitting to be true. Perhaps we all eventually get the name that suits our being, some at birth, some later when the time is right.

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.