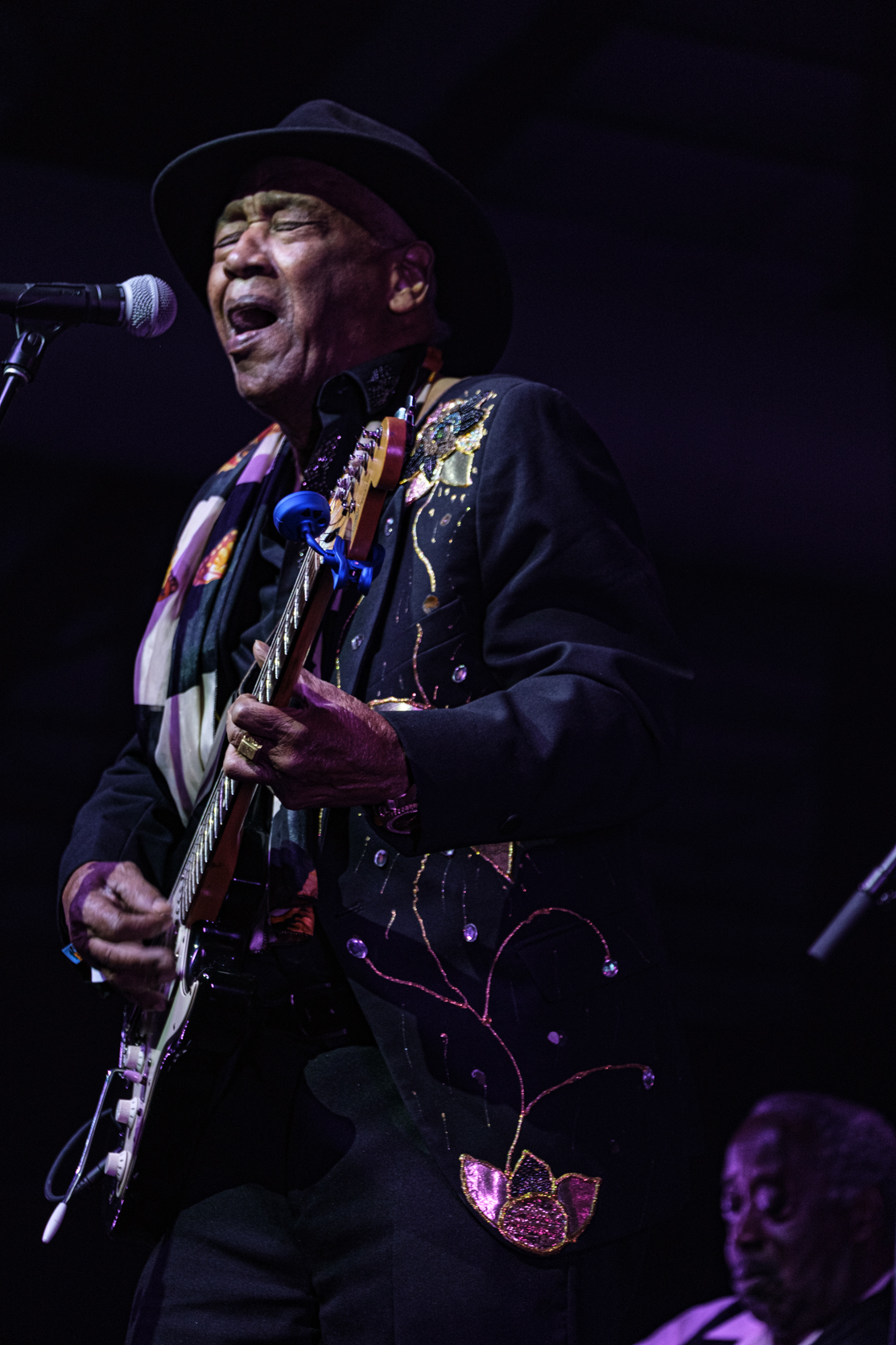

The Invisible Man: Hermon Hitson Might Be the Greatest Guitar Player You’ve Never Heard Of

By Chuck Reece

When Music Maker Foundation took the latest version of our Music Maker Blues Revue to the Telluride Blues & Brews Festival in Colorado, the band included a guitar player and singer from Atlanta named Hermon Hitson. He was brand new to the Music Maker family, but he had a musical track record of more than 50 years, playing with the likes of Jimi Hendrix, James Brown and many others. When Hermon first met the Gospel Comforters — another band we brought to the fest — they all looked at his shoes.

“Where did you get those James Brown boots?” a member asked. “They don’t make those anymore. Only James had those made.”

You, dear reader, have probably never heard of a guitar player named Hermon Hitson, but there he stood, in Colorado, wearing a pair of custom-made boots that no one but James Brown himself and those who played with him could ever put on their feet.

Like those boots, Hermon Hitson himself is unique in the truest sense of the word. No one else is like him. No other human has the wild mix of experiences that make up Hermon’s life. And certainly no one plays the guitar like Hermon does — a mind-bending mix of psychedelic rock, the blues, rhythm & blues and soul music.

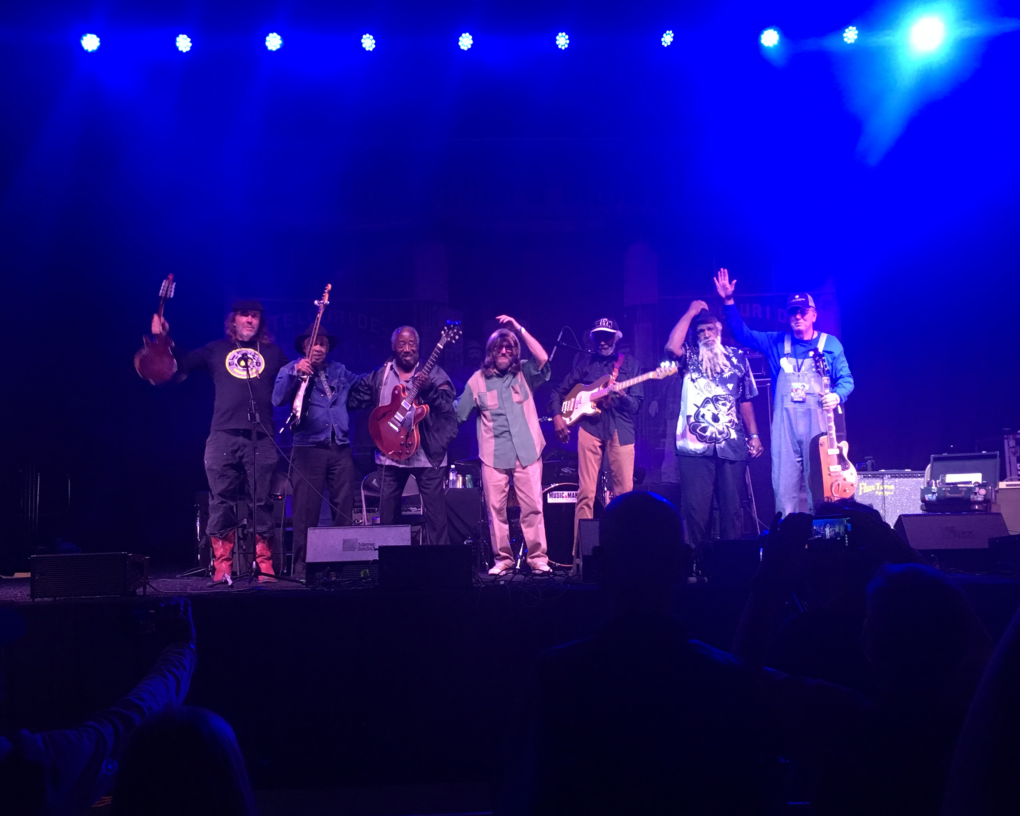

Sam Duffy, brother of our co-founder Tim Duffy and a player of the electric mandolin, joined the Music Maker Blues Revue for their final set at Telluride.

“I played the last three songs on stage with him,” Sam remembers. “We did a set of standards. It was Hermon’s turn, and he said, ‘OK, we’re going to do Howling Wolf’s “Back Door Man.”’ We’re like, ‘OK, cool.’ Then he just launched into this …”

Sam pauses for a long time, seemingly unable to muster the words needed to describe what he experienced playing with Hermon.

“I’m still blown away,” he finally continues. “It was crazy. I’ve never … I can’t really describe it…. It was this psychedelic, LSD-feel blues. It, like, triggered me, back to ‘Wow, I think I’m tripping again.’ It was like, ‘What is going on?’”

One Music

In the music business, there are certain sidemen — players who back the stars — who play with such prowess that they gain fame of their own. By all rights, Hermon Hitson should be one of those people. Over the years, he played with Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Joe Tex, Bobby Womack, Wilson Pickett, Garnet Mimms, Major Lance, Jackie Wilson, the Drifters, the Shirelles, Hank Ballard & the Midnighters and many others. Along the way, he picked up every style of music that was popular in the early years of his career.

Arguably, the original seeds of psychedelic rock were planted after Hitson and Hendrix became running buddies in the early 1960s. Both were playing the Chitlin’ Circuit, tours that would load somewhere between 10 and two dozen African American musicians on a bus and tour the South, playing Black nightclubs. The two spent weeks together, Hermon says.

“Me and Jimi used to stay up all night, sitting on the bed, eating soda crackers and sardines, and drinking Coca-Cola and Pepsi,” Hermon recalls.

He moved from there to straight-up soul music, recording his own compositions — including the luscious “Been So Long” — in Atlanta for labels like Royal, Atco and Minit. As the 1970s rolled in, Hermon wound up playing funk guitar, recording some tracks with the Ohio Players and releasing some of his own funk singles, including the powerful “Ain’t No Other Way,” a number firmly in the James Brown vein.

Every step of Hermon’s life added to his repertoire and guitar prowess — and to his view of music itself. Perhaps it’s best to let him tell that story.

“I was born in Philadelphia in ’43,” he says. “Then my father died, and my mother took me down where her people was, and that was in deep Georgia — a place called Ocilla, Georgia.” The tiny town, with population under 4,000, sits about 80 miles north of the Florida line in south central Georgia.

“I was only listening to country,” Hermon recalls. “And those guys really, really excited me. There was no Black radio for me to hear the Black guys doing music. So, country was all I knew besides gospel.”

To build a better life for her children, Hermon’s mother moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where her brothers were, then soon moved Hermon and his brother there.

“That’s when everything busted out,” Hermon says. “I began to see these guys walking down the streets, man, with the head rags on their heads, with guitars tied around their neck, the harmonica blowing. I would see them sitting in front of me at the barbecue joints. They’re sitting and they’re drinking. These guys influenced me. It was the blues, man. I had the gospel and the country. Now, here I am, and all this mixture became one music to me.”

Back With Jimi in New York

Perhaps it was that fact — that all music became one music in Hermon’s mind — that kept him from making hits of his own in the 1960s and ’70s. No producer ever sat down with Hermon and told him to make the record he wanted to make, to take the pure creativity inside him and express it on vinyl however he chose.

Instead, producers wanted to insert the stylistically versatile Hitson into whatever kind of music they believed most likely to turn into a hit. Living in Atlanta in 1962, Hitson began working with Lee Moses, another soul singer and guitar player. Both of them worked with a producer named Johnny Brantley. Hermon’s first four recordings were issued on the Royal label. “Been So Long,” a slow soul ballad, was chosen as the single. Hermon released several other singles while in Atlanta.

Then, in the mid-1960s, he moved to New York City, where he once again hooked up with Hendrix. Early in 1966, Hermon began work on his own psychedelic rock album under the title “Free Spirit.” Hermon sang and played lead guitar, and Hendrix played bass on a few tracks. Those recordings wound up being the source of a controversy in the 1980s that brought Hermon’s name into the limelight in a different way. The title song of the album, “Free Spirit,” was released on two albums of music allegedly recorded by Hendrix and then “lost” to history.

“That’s my song,” Hermon says today. “Jimi heard it, and he would go to the studio with me when I come to New York, because he was hanging out with Johnny Brantley, too. He [Hendrix] didn’t never play no lead on nothing of mine. And he didn’t sing on nothing of mine. In fact, back then he thought he couldn’t sing. We had to keep pushing him: ‘Man, you can sing. Man, just sing like you. People going to love you for you, man.’”

A few months later Keith Richards and Rolling Stones producer Andrew Loog Oldham fell in love with Hendrix, and brought him back to London with them. Soon after, the Jimi Hendrix Experience came together. The rest is history, a history that Hermon Hitson was not a part of.

He was left in America to play whatever he felt like playing.

Coming Back Into View

Hermon never stopped playing, but his career was mostly limited to nightclub gigs in his hometown of Atlanta. Music Maker did not discover Hermon in his hometown, but through a tip that came from Birmingham, Alabama. Roger Stephenson, vice president of the Magic City Blues Society in Birmingham, told Tim about Hermon during a Music Maker scouting trip through Alabama in the spring of this year. Shortly after, the two met, and Hermon was realistic about where his career stood when he first met Tim.

“He realized he was invisible to everybody,” Tim says.

But Hermon soon agreed to join the Music Maker Blues Revue for its gigs at Telluride in September, and that put him on the road to a new brand of public attention.

The Revue’s longtime musical director and drummer, Ardie Dean, always has the job of learning as much as he can about the musicians who are joining the band and the styles they play.

“Hermon is an interesting fellow,” Ardie says. “He wears a couple different hats. His claim to fame was his ’60s psychedelic era. And then he switched gears in the ’70s and got into a deep groove where he would play some super good funk music. And then, he went into his own thing, which was a combination of blues-based R&B and soul. And he continued on for the next 40 years in that vein of just making his own music, not all blues, just a variety of sort of styles on a limited budget, but it was all his own. So he’s got these three different distinct areas of his career. So when we play with him, we’ve tried to draw out all those stops. We wanted to play some psychedelic. We want him to play some funk. We want to play his new stuff. And that’s why he’s interesting. He’s not a one-trick pony.”

Hermon proved that on the Telluride stage for three days in a row. The gigs lifted his spirits tremendously.

“That was great, man: the scenery and all the beautiful people, man,” he says. “The fans were so great, man. I can’t explain the whole deal of what I felt and what I saw. It was just so beautiful, man. And I would love to do that again.”

Doubtless, now that he is firmly set as a member of the Music Maker family, Hermon will have that chance. And he’ll continue to flabbergast not only the audiences he plays for, but also the musicians he plays with.

Sam Duffy, who still has great difficulty explaining what playing with Hermon felt like, remembers walking off the stage after that last performance in Telluride.

“I’m walking off stage and I’m like, ‘Hermon, how did you … what were you doing on your guitar?’” Sam recalls. “I usually don’t bug the guys. But I just accosted him as we were walking off stage. ‘How did you do that? What is going on here?’ He just smiled at me. He said, ‘I don’t know. I just played the guitar.’”

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.